- CONTENTS:

- Table of ContentsLetter from the Editor1st Source Bank: A Partner from the Great Depression through the Economic RecessionAuthentic Identity: The Essence of How Successful “Ecopreneurs” CommunicateAccounting Ethics Education: An Authentic Value-Based ApproachValues-Based Leadership and Happiness (Enlightened Leadership Improves the Return on People)The Values-Based RevolutionPower, Responsibility & Wisdom: Exploring the Issues at the Core of Ethical Decision-Making and Leadership

- POWER, RESPONSIBILITY & WISDOM: EXPLORING THE ISSUES AT THE CORE OF ETHICAL DECISION-MAKING AND LEADERSHIP

We are trying to improve things. We are trying to make progress. Of course, the concepts behind the words: “improve,” “better,” and “progress” are powerfully values-driven. Organisations and individuals don’t have a problem with change, only with how we perceive progress.

Our success in this area is critically dependent on the quality of our dialogue…DR. BRUCE LLOYD, EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT,

LONDON SOUTH BANK UNIVERSITY, LONDON, UKIntroduction

The objective is simple: “Better decision-making.” The only issue is that there are so many different views over what we mean by “better.” At the core of all decision-making is the need to balance Power with Responsibility, as the vehicle for resolving the “better” question. This article explores why that is so difficult? It also argues that exploring the concept of Wisdom can provide invaluable insights into how to achieve the most effective balance between Power and Responsibility, which is central to what our values mean in practice, as well as how we incorporate ethics into our decision-making.

Wise decision-making also, inevitably, involves moral/ethical choices and this occurs every time we make a decision. Hence, it is not surprising that we find that the comments we might define as Wisdom are essentially comments about the relationship between people, or their relationship with society, and the universe as a whole. These statements are generally globally recognised as relatively timeless and they are insights that help us provide meaning to the world about us. Yet how often it seems to be almost totally ignored in Futurist, Strategy, Knowledge Management, and even Ethics-based, literature. We also appear to spend more and more time focused on learning knowledge, or facts, that have a relatively short shelf life, and less and less time on knowledge that overlaps with Wisdom, that has a long shelf life. Why is that? What can we do about it?

Power and Responsibility

Western sociological and management/leadership literature is full of references to Power. How to get it? How to keep it? And how to prevent it from being taken away? In parallel, but rarely in the same studies, there is also an enormous amount of literature on the concept of Responsibility.

While Power is the ability to make things happen, Responsibility is driven by attempting to answer the question: “In whose interest is the Power being used?” Yet the two concepts of Power and Responsibility are simply different sides of the same coin; they are the Ying and Yang of our behaviour; they are how we balance our relations with ourselves with the interests of others, which is at the core of what we mean by our values. Power makes things happen, but it is the exercise of an appropriate balance between Power and Responsibility that helps ensure as many “good” things happen as possible.

This critical relationship between Power and Responsibility is reinforced by examining how these two concepts interact in practice, through a variety of different management dimensions.

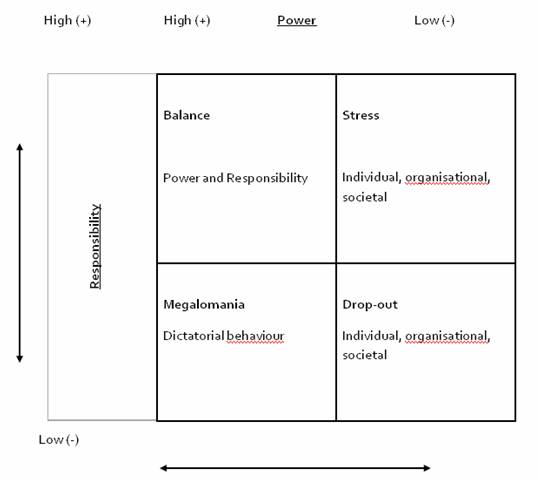

First, it is useful to visualise a two-by-two (Boston) box (see Diagram 1 below), with Power (+&-) along the horizontal axis, and Responsibility (+&-) along the vertical. In one square, where there is a strong Power-driven (+) culture, combined with little sense of Responsibility (-), there is a high probability of megalomaniac or dictatorial behaviour. While another square would combine a high degree of Responsibility (+), with little Power (-), which is a classic recipe for stress. In fact, this is a major cause of relatively unaddressed individual, organizational and societal stress, reinforced by many empowerment programmes that are more concerned with giving individuals more Responsibility than giving them more real authority (i.e., Power). A further square has low levels of both Power (-) and Responsibility (-) producing the net result of “drop-outs,” whether individual, organisational, or societal. This category is often viewed as an attractive option when individuals consider it relative to the alternative to the stress, which is all too often associated with situations where the feeling of impotence is associated with the feeling of Responsibility. The ideal is to work towards the final square where there is an appropriate balance between Power and Responsibility (+/+). Although this compartmentalisation is an inevitable simplification, it does show how the underlying pattern of Power <> Responsibility relationships influence individual behaviour, which is particularly critical in areas related to ethical decision-making.

Diagram 1: Power – Responsibility Relationships

This basic relationship between Power and Responsibility is confirmed from experience in several other organisation/societal dimensions:

1. Organisational culture can be considered as either one that encourages the sharing of information, as opposed to a “Knowledge is Power” culture. (Although I consider it is more appropriate to use the word Information, rather than Knowledge, for reasons that are discussed in more detail later.) Almost all management techniques (Total Quality Management, Learning Organisations, and Knowledge Management, to name but three) are based on the assumption of a sharing knowledge culture and these techniques are unlikely to be effective within a “knowledge is power” culture. Teams, and virtually all other management techniques, flourish best under a Responsibility-driven culture. In addition, as we move further into a knowledge economy, the effective sharing of information/knowledge will become even more critical for all our decision-making whether as individuals, within organisations, or for society as a whole.

2. It is often argued that people oppose change, when the underlying problem is, in fact, that there is a difference of opinion on how to define progress ― or what we mean by “better.” In a culture where those affected by change are either in control, or they trust those driving the change, there is usually general agreement on how progress is defined, and there is little opposition to any change initiatives. The greater the trust levels, the easier it will be to undertake change, simply because there is general agreement that the change will be equated with progress. Despite all the talk of the need for change in many situations, what is really required is the need for greater emphasis on the concept of progress. Unfortunately, it is very rarely the case that all change can be equated with progress. This difference between change and progress is at the heart of most organisational difficulties in this area, partly because the vast majority of change is still top-down driven, and this is, unfortunately, combined with the widespread existence of a Power-driven culture, which has fostered a breakdown in trust in far too many situations.

3. Another important dimension of the Power-Responsibility relationship arises in many organisations where they experience the damaging effects of bullying, corruption, as well as sexism and racism. These problem behaviours are, essentially, in the vast majority of cases, essentially little more than the “Abuse of Power.” If individuals took a more Responsible-driven (i.e., “others focused”) approach to their personal relationships, there would be an enormous reduction in these harmful anti-social behaviours.

4. The issues considered above are also reflected in the language we use to discuss them. Phrases, such as “Corridors of Power,” “Power Struggles,” even “Lusting after Power,” are widely used, but would not attitudes and behaviours be different if the language used was more focused on using phrases such as “Corridors of Responsibility?” Why do we never hear about “Responsibility Struggles?” There are very few, if any, examples of people being accused of “Lusting after Responsibility.” Why not? If Power and Responsibility are two sides of the same coin, shouldn’t the words Power and Responsibility be virtually interchangeable?

The greater the level of a Responsibility-driven, decision-making culture, the more effective and sustainable will be the consequences of that process; and the less regulation will be required to manage the inter-relationship between the various stakeholders. In contrast, more and more regulations will be needed in an attempt to regulate Power-driven cultures, where those regulations are designed, in theory, as an attempt to make the decision-making processes more accountable, and so encourage more responsible behaviour. If we all behaved more responsibly in our relationship with each other, there would be much less pressure for more and more regulation and legislation.

Rights and Responsibilities

In addition, it can be argued that it was a pity that there has been such an emphasis on “Rights” during the twentieth century ― the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Declaration of Human Rights, etc. ― rather than emphasising a combination of “Rights with Responsibilities.” In almost all current ethical debates (as well as legal and other regulatory structures), the ultimate objective is to try to achieve the appropriate balance of Rights and Responsibilities. If individuals behaved more responsibly and ethically towards each other, it would be much more likely that the net result would be a higher standard of ethical decision- making overall. This is a classic case where the outcome and process are closely interlinked.

In the context of the above comments, it is worth mentioning that probably 90% of violent behaviour arises because there is an imbalance, or discontinuity, between Power (self-focused), and our sense of Responsibility (others-focused), which leads to a breakdown in the ability to communicate effectively between those involved. This breakdown becomes even more acute, and problematic, if it is combined with an inability to undertake a constructive dialogue in the first place.

Leadership is nothing more than the “well-informed, Responsible, use of Power.” The more the leadership-related decisions are Responsibility-driven (i.e., the more they are genuinely concerned with the wider interest), not only will they be better informed decisions, but the results are much more likely to be genuinely reflect the long-term interests of all concerned, which also happens to be a sound foundation for improving their ethical quality.

Wisdom

In essence, the above leadership definition is exactly what could also be called “Wise Leadership.” In this context, the concepts of leader, leading, and leadership are used interchangeably, although it could be argued that leaders are individuals (including their intentions, beliefs, assumptions, etc.), while leading reflects their actions in relation to others, and leadership represents the whole system of individual and social relationships that result in efforts to create change/progress. However, the above definition can be used to cover the integrated inter-relationship of those three dimensions.

There is an enormous amount of literature that explores Wisdom, and this can provide useful insights into what works and what doesn’t? However, partly because, for various reasons, the word Wisdom has been widely misused and misunderstood, it might be useful to explain how I got involved in exploring this generally neglected dimension of thinking about how people, organisations, and society work well in practice.

My background is Science, with Engineering and Business degrees, and a career in Industry and Finance that ended up with my writing and lecturing on Strategy, where I consider Strategy to be about “understanding what makes organization, people, and society work,” and what helps them work “better,” recognising that “better” is a values-driven word. In other words, I have a very practical approach to these issues.

It is worth emphasizing that I didn’t have a classical education and, perhaps I should also mention that in this journey and discussion, I have no religious agenda.

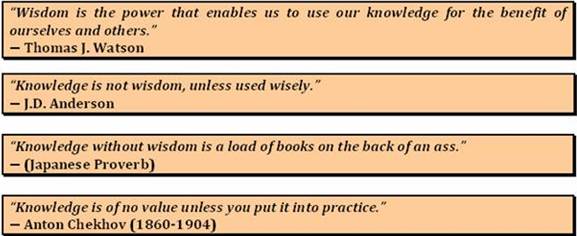

Reflecting on those earlier experiences have led to exploring the questions: What do we mean by Wisdom? And why it is an important subject for both organizations and society? This interest arose particularly from two directions. First, my interest in strategy in the early 1990s was very influenced by the widespread discovery (or more strictly re-discovery) of the importance of Organisational Learning, (largely thanks to the work of Peter Senge and his book The Fifth Discipline) and this is reflected in two relevant wise quotes:

and

The net result of this emphasis on learning naturally leads to the question: What is important to learn? Trying to answer that question partly led to the massive growth in the Knowledge Management Industry. I was brought up on the Data/Information/Knowledge pyramid, which ended with Wisdom at the top. Yet most Knowledge Management books, with a few notable exceptions, do not discuss the role and importance of Wisdom.

The second dimension arose in the late 1990s when I was involved in a number of “Futures”-related activities preceding the new Millennium. In fact, the recent move into the new Millennium was probably the most focused point in human history for exploring these questions. In these discussions, there was an enormous emphasis on technology. But I found that almost no one had studied what we had really learned over the past two or three thousand years that was really important to pass onto the next generation ― i.e., Wisdom. (This led to a project for the World Future Society, “Messages for the New Millennium” ― (http://wfs.org)).

Wisdom is something everybody seems to talk about. We all appear to want more of it, yet few people appear to reflect on what Wisdom really is, especially in management/leadership literature. And there is little consideration of how can we learn Wisdom more effectively? An over-riding objective of these brief comments is simply that it would be very useful for us to try to rehabilitate the word/concept of Wisdom.

Wisdom Definition

But what do we really mean by Wisdom? According to the Wikipedia (5/8/05) entry for Wisdom:

“Wisdom is often meant as the ability and desire to make choices that can gain approval in a long-term examination by many people. In this sense, to label a choice ‘wise’ implies that the action or inaction was strategically correct when judged by widely-held values. … Insights and acts that many people agree are wise tend to:

- arise from a viewpoint compatible with many ethical systems;

- serve life, public goods or other impersonal values, not narrow self-interest;

- be grounded in but not limited by past experience or history and yet anticipate future likely consequences; and

- be informed by multiple forms of intelligence ― reason, intuition, heart, spirit, etc.”

More briefly, Wisdom can be considered as: “Making the best use of knowledge … by exercising good judgement … the capacity to realise what is of value in life for oneself and others. ...” Or as “the end point of a process that encompasses the idea of making sound judgements in the face of uncertainty.” Of course, Wisdom is one thing, “being wise” is quite another. Being wise is certainly more than the ability to recycle Wisdom. In essence, “being wise” involves the ability to apply wisdom effectively in practice.

Wisdom Statements

Wisdom statements are those that appear to be useful in helping us all make the world a better place in the future. They are not absolute statements; they are simply statements that reflect our understanding of behaviour patterns that appear to work in a positive, sustainable, direction. But a statement of Wisdom is only useful if it also checks out with our own experiences.

Of course, that relatively simple objective is not quite as easy as it sounds for at least two reasons: Firstly, the word “better” inevitably means that we are involved in considering the whole subject of values. A critical part of the content of any Wisdom statement is the extent to which it incorporates judgments about values. In fact, that is a critical part of the definition of what we mean by Wisdom. That does not mean that all statements that reflect values can be defined as Wisdom; the extra dimensions required are that they are widely accepted and have “stood the test of time.” In addition, while all wisdom is reliable, useful, information, not all reliable information can be considered as Wisdom; they are insights into values, people, and relationships that work. They are not simply technical statements that have no human or relationship dimension.

Secondly, it is important to recognise that in trying to “make the world a better place for us all” can easily run into potential areas of conflict. For example, making things “better” for some people can be at the expense of making it worse for others. Much of the conflict in this area is because different people use different time horizons when they talk about the future. Some people are obsessed with tomorrow, whilst others are primarily concerned with what they perceive to be the needs of the next hundred years. How, or whether, differences in perspectives are resolved is critically dependent on the quality of dialogue between the parties.

In my view, there are no absolute answers; consequently the only way to make progress is to try to ensure that the quality of the dialogue between all concerned (i.e., all the stakeholders) is as effective as possible. In the end, the quality of our decisions depends on the quality of our conversations/dialogue; that is not only dialogue about information but, perhaps even more importantly, it is about what is the best way to use that information. In other words it is about our values. Dialogue facilitates both the transfer of technical knowledge as well as being an invaluable part of personal development. Having a quality dialogue over values is not only the most important issue we need to address, but it is often the most difficult. In this area, there is a paradox with the concept of passion, the importance of which is emphasized in much current management literature. If this passion is exhibited by Power-driven persons who tend to think they have all the answers ― and they are all too often not interested in listening ― then holding a positive dialogue can easily become problematic! The only way to “square that circle” is to ensure that all the other people involved are convinced of their integrity and that they are reflecting a genuine concern for the wider interest in the decisions that are taken. The greatest challenge that most organisations face is how to manage effectively Power-driven, passionate, people in such a way that their priority is encouraged to be consistent with the long-term interests of the organisation as a whole, rather than just with their own personal interests. Incorporating this wider (Responsibility-driven) interest into our decision-making at all levels, irrespective of whether they are personal, organisational or societal, is the ultimate test of both values and leadership.

Re-interpreting the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom Relationship

The traditional approach to the data-information-knowledge-Wisdom link sees a close relationship within a pyramid that starts with data at the bottom, moves through information and knowledge, to end with Wisdom at the top, giving, in theory, greater “added value” as we move up that pyramid. In my view, this progression has a fundamental flaw arising from the fact that the relationship between these four items is not linear and there is no basic step-by-step, linear, movement up the pyramid from data to Wisdom. The mechanistic view of that progression is partly a reflection of the Newtonian tradition, repackaged by the Management Science of Taylorism.

In practice, the integration of all four elements requires at least one, if not two, quantum (/qualitative) jumps. Information can certainly be considered a “higher” form of data, as it provides greater context and hence, greater meaning. However, the transformation of information into knowledge requires the first quantum jump. A book that describes how a jet engine works is an example of information. It is only when information is actually used that it is turned into knowledge. In a similar way, science produces “value” and “values”–free information. It isn’t until something is done with that information that we need to recognise that all our choices (/decisions) are concerned with “adding value,” as well as being values-driven, and these decisions are driven by our perception that one alternative is somehow “better” than another. In essence, knowledge is information in use and, of course, it is through its use, and through the feedback learning loop, that you gain further information, which then gets turned into even more legitimate knowledge-based action. Overall, this is a never ending, dynamic process.

But where does Wisdom come in? Wisdom is the vehicle we use to integrate values into our decision-making processes. It is one thing to turn information into knowledge that makes things happen through its use, but it is quite another thing to make the “right” (/“good”/“better”) things happen. How we actually use knowledge depends on our values. Instead of moving up from data/information/knowledge to Wisdom we are, in parallel, moving down from Wisdom to knowledge ― and that is how we incorporate our values into our decision-making. Hence we can see the application and relevance of what is generally called Wisdom. It is only justified to consider that decisions can be reduced to a cost/benefit analysis if it is possible to quantify all the “values” elements within the equation in monetary terms. In the past, values have been included implicitly, whereas today that dimension invariably needs to be made much more explicit. All decisions involve the integration of the economics dimensions of “added value,” with the ethical (i.e., “right”) dimension of “values.”

Of course, this is a dynamic process and there is continual feedback from the experience of our actions into whether we need more information. But what and how much further information is required is also a values-influenced decision. How values are assessed and applied, both as the ends and means, are critically important dimensions in all our decision-making.

Our values/Wisdom define the limits of what are considered acceptable choices in the first place and those decisions determine our knowledge/action priorities. These priorities then determine what information is required in order to try to ensure that the decision is as well-informed as possible. In turn, that need for information determines what further questions have to be asked about what additional data is required. It also needs to be recognised that the way the word (/concept) Wisdom, has been used in the past has not always helped this process.

We need to start with Wisdom(/our values) as our base, which provide the framework within which to manage knowledge, and so on through the pyramid to information and data. Consequently, without a sound base at one level, it is difficult to manage effectively the next layer up (or down): Knowledge as information in use and Wisdom as the integration of knowledge and values to produce wise action. This is confirmed by the comments below:

Many of the important messages about the state and future of the Human Race were made over a thousand years ago, in China, the Middle East, and other early sophisticated societies. In fact, Wisdom insights are very similar irrespective of which part of the world identified as their source because they consist of statements about relationships between people ― either individually or collectively, in societal context or about our relationship with the universe as a whole ― that they have “stood the test of time.”

Learning

Wisdom is by far the most sustainable dimension of the information/knowledge industry. But is it teachable? It is learned somehow, and as far as I know, there is no “values”/Wisdom gene. Consequently, there are things that we can all do to help manage the learning processes more effectively, although detailed consideration of these are outside the scope of this paper.

We need to recognise that the more change that is going on in society, the more important it is that we make sure that our learning is as effective as possible. That is the only way we have any chance of being able to equate change with progress. If we want to have a better future the first ― and most important ― thing that we have to do is improve the quality and effectiveness of our learning.

We are trying to improve things. We are trying to make progress. Of course, the concepts behind the words: “improve,” “better,” and “progress” are powerfully values-driven. Organisations and individuals don’t have a problem with change, only with how we perceive progress. Our success in this area is critically dependent on the quality of our dialogue as discussed earlier. Unfortunately, it is not easy to be optimistic about current trends, when the media is so focused on sensationalism and confrontation.

Wisdom Insights

Some examples of statements about Wisdom that not only reflect the points made above, but provide additional insights into the meaning and usefulness of the word, would include:

- “Knowledge is a process of piling up facts; Wisdom lies in their simplification.”

― Martin H. Fisher - “Wisdom outweighs any wealth.” ― Sophocles

- “Wisdom is the intelligence of the system as a whole.” ― Anon

- “Wise people through all laws were abolished would lead the same life.”― Aristophanes

And some of the general Wisdom messages that we might like to pass onto future generations might include:

- "By doubting, we come to examine, and by examining, so we perceive the truth."

― Peter Abelard - “The price of greatness is responsibility” ― Winston Churchill

- "If you won't be better tomorrow than you were today then what do you need tomorrow for?" ― Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (1772-1811)

- "You must be the change you want to see in the world." ― Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948)

- "The purpose of studying history is not to deride human action, not to weep over it or to hate it, but to understand it -- and then to learn from it as we contemplate our future.” ― Nelson Mandela

- “Concern for others is the best form of self interest” ― Desmond Tutu

What are the implications of these ideas for us all?

A Wise Society

In recent years we have seen considerable effort to move people from the idea of “Working Harder” to “Working Smarter.” But what is really needed is to move beyond “Working Smarter” to “Working Wiser.” We need to move from “The Knowledge Society” to “The Wise Society.” And, the more we move along that progression, the more we need to recognise that we are moving to a situation where the important issues primarily reflect the quality of our values, rather than the quantity of our physical effort. If we want to improve the quality of our decision- making, the focus needs not only to be on the quality of our information but, perhaps even more importantly, on the “right” use of that information, hence the importance of improving the dialogue-related issues mentioned earlier.

Stakeholder analysis can help understand the map of the Power/Responsibility relationships within decision-making processes. All decisions require trade-offs and this involves judgement between the interests of the various stakeholders, within a framework of a genuine concern for the long term ― and the wider interest. It is also the case that where there is no common agreement over objectives, values are invariably the dominant agenda in any discussion. It is here that Wisdom reflected in both content, and process, can be critical. How often do we seem to be either obsessed with technology ― or so focused on the experience of the here-and-now ― that the issue of Wisdom appears to be virtually ignored? Are we really focused on what is important, rather than on just what is easy to measure?

One reason for the recent obsession with an information-based approach is because that provides a relatively easy framework within which to procure agreement of decisions. Any focus on the values dimension can make decision-making much more problematic. There are two answers to such a view: First, values are implicitly involved in all decision-making and all we are doing is making the discussions about the values dimension more explicit, a process that is, after all, at the core of Knowledge Management. It is also through making information/knowledge more explicit that we can improve the effectiveness of our learning processes. Secondly the evidence suggests that there is much more agreement across all cultures and religions about fundamental human values (and Wisdom) then is generally recognised.

Conclusion

Finally, I come back to the point made at the beginning. Why are we interested in Ethics and the Future? The answer is, simply that we are concerned with trying to make the world a “better” place. But for whom? And how? To answer both questions we need to re-ask fundamental questions: Why do we not spend more time to ensure that the important messages that we have learned in the past (Wisdom) can be passed on to future generations? How do we ensure these messages are learned more effectively? These are critical strategy questions, as well as being at the very foundation of anything we might want to call “The Knowledge Economy,” although what is really needed is to focus on trying to move towards a concept closer to “The Wise Economy.” This focus naturally overlaps with the greater attention recently being given to values/ethical-related issues and “the search for meaning” in management/leadership literature.

Overall, Wisdom is a very practical body of sustainable knowledge (/information) that has an incredibly useful contribution to our understanding of our world. Such an approach would enable us all make “better” (/wiser) decisions, lead “better” lives, and experience wiser leadership, particularly in areas that involve explicit, or implicit, ethics and values-related issues which are themselves closely linked to establishing more appropriate relationships between Power and Responsibility.

If we cannot take Wisdom seriously we will pay a very high price for this neglect. We need to foster greater respect for other people, particularly those who have views, or reflect values, with which we do not agree. This requires us to develop our capacity to have constructive conversations about the issues that divide us and that, of itself, would go a long way to ensure that we improve the quality of our decision-making for the benefit of all in the long term.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Achenbaum, W.A. (1997). The Wisdom of Age ― An Historian’s Perspective. Institute on Aging, University of Michigan, April 3.

Ackoff, R.L. (1989). From Data to Wisdom, Presidential Address to ISGSR, June 1988, R.L Journal of Applied Systems Analysis. 16: 3-9.

Ardelt, M. (2000). Intellectual Versus Wisdom-Related Knowledge: The Case for a Different Kind of Learning in the Later Years of Life. Educational Gerontology, 26: 771-789.

Ardelt, M. (2003). Empirical Assessment of a Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale. Research on Aging, 25:3, May, 275-324.

Ardelt, M. (2004). Wisdom as Expert Knowledge System: A Critical Review of a Contemporary Operationalization of an Ancient Concept. Human Development, 47: 257-285.

Ardelt, M. (2005). How Wise People Cope with Crises and Obstacles in Life. Revision, 28:1, Summer, 7-19.

Atlee, T. (2002/3). Empowered Dialogue Can Bring Wisdom to Democracy. (as “Wisdom, Democracy and the Core Commons” in Earthlight, Fall/Winter (www.earthlight.org)).

Awbrey, S. M, and Scott, D.K. (1995). Knowledge into Wisdom: Unveiling Inherent Values and Beliefs to Construct a Wise University.

http://www.umass.edu/pastchancellors/scott/papers/papers.html.

Baltes. P.B. and Kunzmann U. (2004). The Two Faces of Wisdom as a General Theory of Knowledge and Judgement about Excellence in Mind and Virtue vs. Wisdom as Everyday Realization in People and Product. Human Development, 47:290-299.

Baltes, P.B, Staudinger, U.M, Maercker A, and Jacqui Smith, J. (1993). People Nominated as Wise: A Comparative Study of Wisdom-Related Knowledge. Psychology and Aging, 10:2, 155-166.

Baltes, P.B, and Staudinger, U.M, (2000). Wisdom: A Metaheuristic (Pragmatic) to Orchestrate Mind and Virtue Toward Excellence. American Psychologist, 55:1, 122-136.

Bellinger, G, Castro, D, and Mills, A. (2004). Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom. Systems Thinking.

Bezold, C, Bettles, C, and Fidler, D. (2008). Wiser Futures: Using Futures Tools to Better Understand and Create the Future. The Institute for Alternative Futures (Presentation to 2008 Annual Conference of World Future Society).

Bierly III, P. E, Kessler, E. H. And Christensen, E. W. (2000). Organizational Learning, Knowledge and Wisdom. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 13:6, 595-618.

Bluck, S. and Gluck, J. (2004). Making Things Better and Learning a Lesson: Experiencing Wisdom Across the Lifespan. Journal of Personality, 72:3, June, 543-572.

Brown S.C, and Greene, J.A. (2006). The Wisdom Development Scale: Translating the Conceptual to the Concrete. Journal of College Student Development, Jan./Feb, 47:1, 1-19.

Case, P, and Gosling, J. (2007). Wisdom of the Moment: Pre-modern Perspectives on Organizational Action. Social Epistemology. Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21: 2, April- June, 87-111.

Chatterjee, D. (2006). Wise Ways: Leadership as Relationship, Journal of Human Values. 12; 153-160.

Curnow. T (2000). Wisdom and Philosophy. Practical Philosophy, March, 3.1, 10-13.

Gluck, J, Bluck S, and Baron, J. (2005). The wisdom of experience: Autobiographical narratives across adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29 (3), 197-208.

Hall, S.S. (2007). The Older-and-Wiser Hypothesis. The Times Magazine, May 6.

Hammer M. (2002). The Getting and Keeping of Wisdom: Inter-Generational Knowledge Transfer in a Changing Public Service. Research Directorate, Public Service Commission of Canada, October.

Jearnott, T.M. (1989). Moral Leadership and Practical Wisdom. International Journal of Social Economics, 16,:6, 14-38.

Kekes, J. (1983). Wisdom. American Philosophical Quarterly, 20:3, July, 277-286.

Kessler, E. H. (2006). Organizational Wisdom: Human, Managerial, and Strategic Implications. Group & Organization Management, 31:3, 296-299.

Korac-Kakabadse, N, Korec-Kakabadse, A, and Kouzmin, A. (2001). Leadership Renewal: Towards the Philosophy of Wisdom, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 67:2, June, 207-227.

Kűpers W.M. (2007). Phenomenology and Integral Pheno-Practice of Wisdom in Leadership and Organization, Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21:2, April-June, 169-193.

Leggat, S.C. (2003). Turning Evidence into Wisdom. HealthcarePapers, 3 (3), 44-48.

Lombardo, T. The Pursuit of Wisdom and the Future of Education, www.cop.com/LombardoWFSarticle01.doc.

Lynch, R.G. (1999). Seeking Practical Wisdom. The Journal of Business History Conference, 28:2, Winter, 123-135.

Malan, L. C. and Kriger, Mark P. (1998). Making Sense of Managerial Wisdom. Journal of Management Inquiry, 7:3, September, 242-251.

Marchand, H. (2003). An Overview of the Psychology of Wisdom. Prometheus Research Group.

www.prometheus.org.uk/Files/MarchandOnWisdom.

Maxwell, N. Can the World Learn Wisdom? www.pelicanweb.org/Solisustv03n04.html

MacDonald, C. The Wisdom Page, www.cop.com/wisdompg.html

McKenna, B and Rooney, D. (2007). Critical Ontological Acuity as the Foundation of Wise Leadership, 6th Annual International Studying Leadership Conference, Warwick Business School. McKenna, B and Rooney, D. (2005). Wisdom Management: Tensions between theory and practice in practice. Knowledge Management in Asia Pacific Conference; Building a Knowledge Society School of Information Management and the School of Government, Victoria University of Wellington, November.

McKenna, B, Rooney, D. and Liesch (2006). Beyond Knowledge to Wisdom in International Business Strategy. Prometheus, 24:3, September, 283-300.

McKenna, B, Rooney, D, and Bos, R. T (2007). Wisdom as the Old Dog...with New Tricks. Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21:2, April- June, 83-86.

McKenna, B and Rooney, D. (2007). Critical Ontological Acuity as the Foundation of Wise Leadership. The 6th Annual International Studying Leadership Conference Warwick Business School: Purpose, Politics and Praxis, 13th/ 14th December.

Roca, E. (2007). Intuitive Practical Wisdom in Organizational Life, Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21:2, April-June, 195-207.

Rooney, D and McKenna, B. (2005). Should the Knowledge-based Economy be a Savant or Sage? Wisdom and Socially Intelligent Innovation, Prometheus, 23:3, September.

Rooney, D and McKenna, B. (2007). Wisdom in Organizations: Whence and Whither. Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21; April-June, 113-138.

Rowley, J. (2006). What do we need to know about wisdom? Management Decision, 44:9, 1246-1257.

Rowley, J. (2006). Where is the wisdom that we have lost in knowledge? Journal of Documentation, 62:2, 251-270.

Small, M.W. (2004). Wisdom and now managerial wisdom: do they have a place in management development programs? Journal of Management Development, 23:8, 2004, 751-764.

Smith J. (1989). Feminist Spirituality: The Way of Wisdom, British Journal of Religious Education, 12:1, 11-14.

Statler, M, Roos, J, and Marterey, R (2005). Practical wisdom: re-framing the strategic challenge of preparedness. Wisdom, Ethics and Management Stream Critical Management Studies Conference. July.

Statler, M, and Karin Oppegaard, (2007). Practical Wisdom: Integrating Ethics and Effectiveness in Organizations, in Business Ethics as Practice, Representation, Reflexivity and Performance, Edited by Carter, C, Clegg, S, Komberger, M, Laske S. and Messner, M, Edward Elgar, 169-189.

Statler, M, Roos, J, and Victor, B. (2007). Dear Prudence: An Essay on Practical Wisdom in Strategy Making, Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21:2, April-June, 151-167.

Staudinger, U.M, Smith, J, and Baltes P.B. (1992). Wisdom-Related Knowledge in a Life Review Task: Age Differences and the Role of Professional Specialization, Psychology and Aging, 7:2, 271-281.

Staudinger, U.M (1999). Older and Wiser? Integrating Results on the Relationship between Age and Wisdom-related Performance, International Journal of Behavioural Development, 23:3, 641-664.

Staudinger, U.M and Pasupathi, M. (2003). Correlates of Wisdom-Related Performance in Adolescence and Adulthood: Age-Graded: Differences in “Paths” Toward Desirable Development, Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13 (3), 239-268.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). A Balance Theory of Wisdom, Review of General Psychology, 2:4, 347-365. Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Why Schools Should Teach for Wisdom: The Balance Theory of Wisdom in Educational Settings, Educational Psychologist, 36:4, 227-245.

Sternberg, R. J. (2001). How Wise is it to teach for Wisdom? R. Sternberg, Educational Psychologist, 36:4, 269-272.

Sternberg, R. J. (2002). It’s Not What You Know, but How You Use It: Teaching for Wisdom, The Chronicles of Higher Education, June 28.

Sternberg, R. J. (2004). Words to the Wise about Wisdom? Human Development, 47:286-289.

Webster, J.D. (2007). Measuring the Character Strength, International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 65:2, 163-183, www.wisdomcentredlife.com.

Wisdom, (2007). Special issue of London Review of Education, 5:2, July, including: From knowledge-inquiry to wisdom-inquiry: is the revolution underway? Nicholas Maxwell; Commercial influences on the pursuit of wisdom, Leemon McHenry; Teaching for wisdom: What matters is not just what students know, but how they use it, Robert Steinberg et al; Wisdom and life-long learning in the twenty-first century, Richard Trowbridge; Wisdom remembered: Recovering a theological vision of wisdom for the academe, Celia Deane-Drummond; Shakespeare on wisdom by Alan Nordstrom; and Coda: Towards the university of wisdom, Ronald Barnett, as well as an Editorial, Wisdom in the university, by Nicholas Maxwell and Ronald Barnett.

Wisdom, (2008). Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, 8 Jan.

Wisdom in Management, (2007). Special issue of Social Epistemology: A Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Policy, 21:2.

Wisdom Society Survey Results. (2002). January.

World Wisdom Rising, (2007). Special issue of Kosmos, Fall/Winter.

Wright, A. (2003). The Contours of Critical Religious Education: Knowledge, Wisdom, Truth, British Journal of Religious Education, 25:4, 279-291.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Professor Bruce Lloyd spent over 20 years in industry and finance before joining the academic world a decade ago to help establish the Management Centre at what is now London South Bank University. He has a Degree in Chemical Engineering; an MSc (Economics) (/MBA) from the London Business School and a PhD (by published work) for his work on “The Future of Offices and Office Work: Implications for Organisational Strategy.” He has written extensively on a wide range of strategy/futures-related issues, and undertaken over 30 interviews on leadership for LODJ, as well others for “The Tomorrow Project Bulletin.” He was also the U.K. coordinator for the ACUNU “Millennium Project” from 1999-2005. The focus of his recent work has been on the relationship between Wisdom and Leadership, and the role of Wisdom in Knowledge Management.