- CONTENTS:

- Letter from the EditorTable of Contents"Smart"Change in Strategy: IBM’s Response to Challenging Times IBM and the Future: Building a Smarter PlanetOliver Winery and the Recipe for Values-Based Leadership: People, Product and PlaceHolistic Leadership: A Model for Leader-Member Engagement and Development A Tale of Two Cultures: Why Culture Trumps Core Values in Building Ethical OrganizationsLeadership: The Tabletop Concept The Leader as Moral Agent: Praise, Blame, and the Artificial Person

- HOLISTIC LEADERSHIP: A MODEL FOR LEADER-MEMBER ENGAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT

K.Candis Best,

JD,MBA, MS, PH.D

Educator/Consultant

Brooklyn, NYIntroduction

This paper presents a model of holistic leadership that is proposed for inclusion with the integrative class leadership theories. It positions holistic leadership as a synthesis of full participation models and developmentally-oriented leadership theories by building upon theories of holistic development. To support its thesis, it begins with an overview of the evolution of leadership theory. Holistic leadership is then defined with its distinguishing elements placed within the context of contemporary leadership literature. The paper concludes with a statement of the theory's fundamental assumptions, its implications for leadership development, and its potential as a supporting framework for future research.

To lead is to inspire others to realize their best potential. While many other definitions of leadership exist, leadership practitioners who meet this standard are likely to be successful more often than not. This paper offers an emergent theory of leadership built upon the class of theories most closely aligned with this goal. It then integrates them with theories of holistic development that offer insight into the most effective ways to access the best potential of enterprise members.

Leadership Paradigms

As Lussier and Achua (2007) note, leadership has evolved over the past sixty years to produce four major paradigms: trait, behavioral, contingency, and integrative. In some respects, each paradigm shift emerged as an evolutionary consequence of both the strengths and the limitations of the paradigm that preceded it - each in its own way offering a perspective on how to inspire that best potential in the individuals and groups being led.

Of these paradigms, the integrative class which includes transformational, servant, and authentic leadership theories, builds upon behavioral, trait, and contingency theories by extending the leader's impact beyond task fulfillment to the process of leadership itself. The expectation is that by attending to the motivational needs of followers, better outcomes are likely to ensue. However, despite the soundness of this premise, translating these theories into practices that deliver consistently superior results remains a challenge for most practitioners. This paper associates the cause with three perceived limitations of the current crop of integrative theories:

- They do not extend themselves far enough into the realm of follower motivation;

- Many continue to rest the locus of causality in leadership processes with the leader; and

- Most do not fully explore the systems implications of the leader, led, and context triad.

Therefore, an opportunity exists for a leadership theory that addresses these shortcomings.Holistic leadership proffers seven fundamental assumptions about the nature of effective leadership:

- Successful outcomes result from an orientation toward development.

- The healthiest and most productive development is done collaboratively.

- The leadership unit shapes the context of collaboration.

- The core leadership unit is the individual, which makes every participant a leader within his or her own sphere of influence.

- The intrinsic desire for meaningful purpose suggests that every individual wants to realize his or her best potential.

- Holistically-led collaboration requires that the participant's right to self-determination be respected.

- The exercise of self-determination in a way that realizes the individual's best potential, results from an iterative process that must be supported.

This paper presents holistic leadership as that next step in the theoretical progression of the integrative paradigm. It does so by drawing upon holistic development theory and its implications for elevating the role of self-determination and collaborative development to a position that is inextricable from successful leadership practice. This contention will be supported first by an overview of the evolution of leadership theory with an emphasis on the connecting strands that link other classes of leadership theory with integrative theories of leadership. From there, a theory of holistic leadership will be presented in sufficient detail to distinguish it from existing theories and articulate its potential as a model for leader, leadership, and organizational development.Evolution of Leadership Theory: Then to Now

The historical view of leadership known as the Great Man Theory reflected two notions: (1) there were inherent, instinctual and perhaps even bio-genetic factors that preselected some for leadership; and (2) that the circumstances that elicited leadership behavior also acted as catalysts propelling those best suited to evolve into leadership positions (Bass & Bass, 2008). In this way, great man theories anticipated both the trait and contingency theories that were to follow. The search for qualities most commonly found in great leaders led to an interest in leadership traits and behaviors that could be measured. It was only upon the inability to find an empirically validated list of traits dispositive of leadership proficiency that other explanations were explored. However, the shift from great man to (and subsequently away from) trait and behavioral theories did not nullify their contributions to what we know to be true about leadership.

Sixty years of leadership research has established that the personality of the leader cannot be wholly excised from the leadership discourse or the outcomes that leadership produces. Instead, trait and behavioral theories served as a pivot point for contingency-based theories that place leadership in the context of leader, follower, and situation (Lussier & Achua, 2007). Indeed, situational leadership theories emerged out of the recognition that their trait and behavioral predecessors failed to address the context variable. As such, situational theories were instrumental in explaining why the presence of specific traits and behaviors in a leader could not consistently predict leadership results. However, there are an infinite number of situations with which a leader may be confronted.

They can be internal or external to the organization; relate to economic, production, or personnel issues; and require chronic, acute, or crisis-level intervention. Further, these situations rarely emerge in isolation. This results in leadership practices that must be evaluated through ever more byzantine constellations of context. What emerged from this dilemma was a shift in perspective from "leadership as performance" to "leadership as interaction" - the thread that not only links but leads from trait, behavioral, and contingency theories to the integrative paradigm.

The Personal Touch

Contingency leadership theory expressly linked personality traits and behaviors to situational context as a mechanism for explaining and then predicting which leadership styles would work best in different situations (Lussier & Achua, 2007). As other situation-indexed leadership theories were developed, the leader's ability to motivate staff toward higher levels of performance emerged as a central theme. Whether by accident or design, these new areas of inquiry had the effect of elevating the needs and desires of the employee and making them a functional element of leadership. From there, it took only a small leap for leadership theory to integrate these concepts into models that emphasized the personality traits and behaviors that motivated and inspired staff.

Transformational, Authentic, and Servant Leader Models

Once the connection between leadership effectiveness and employee motivation was established, leadership research migrated toward isolating the personality traits present in inspiring leaders as well as the behaviors that led to staff motivation. The nexus between charismatic leaders and transformational leadership was a natural outcome of this line of investigation. Charismatic leaders are defined by high levels of energy and enthusiasm as well as strong ideals and superior communication skills that engender loyalty, devotion, and commitment from followers (Nahavandi, 2009). This kind of leader-follower interaction when positively directed supports the norms that leadership scholars associate with transformational leadership.

It is generally accepted that transformational leadership is defined by four criteria: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration (Bass & Bass, 2008; Chemers, 2000; Judge & Bono, 2000; Lussier & Achua, 2007; Nahavandi, 2009; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). These elements synthesize the findings of expectancy, leader-member exchange, and other transactional theories with increasingly popular schemas hinging on the nature and quality of leader/led interactions. Specifically, a growing emphasis on the importance of emotional intelligence (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2002) and leading with heart (Kouzes & Posner, 2002) when added to the imperative of involving employees in the conditions of their work, were crystallized in the transformational leadership profile.

Servant and authentic leadership theories take this profile and add a values orientation. Servant leadership is premised on the equality of all participants in an employment relationship. While hierarchical structures may formally exist, the servant-leader model eschews dominating or controlling tactics of supervision in favor of employee empowerment (Daft, 2008). Lessons learned from the contingency paradigm of leadership theories make clear that certain contexts are less amenable to a servant leadership model than others. Nonetheless, servant leadership and its companion theory of stewardship heavily favor a participatory style of leadership that has proven successful under the right conditions (Walumbwa, Hartnell & Oke, 2010).

Finally, authentic leadership emphasizes the values system of the leader and its role in leading from a base of self-awareness, integrity, compassion, interconnectedness, and self-discipline (Nahavandi, 2009). Clawson (2009) advances a similar concept that he calls Level Three leadership. The third level in Clawson's model refers to the role that values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations (VABE) play in the behavior of the leader and the led. Taken together, the progression of leadership theories over the last half-century can be viewed as a cascade and an evolution with each set of theories being enlarged by the theories that followed it. However, despite the compelling perspectives offered by the current iteration of leadership theories, a gap remains.

The prevailing views of leadership present it in dialectical terms (Popper, 2004). The leader's relationship to the led, the team to the organization, the goal relative to the context - leadership interactions are reflexively treated as a series of causes and effects. However, in reality these interactions are typically nonlinear. This helps to explain why achieving the most desirable leadership outcomes remains unpredictable despite the compelling theses offered by situational and integrative leadership theories. Every individual, entity, or event that is impacted by a leadership process produces its own effects through the idiosyncratic responses being generated. Accordingly, however else leadership is defined, it must also be regarded as a "complex, dynamic and adaptive process . . . integrated" across a "broad range of elements" (Magnusson, 2001, p. 154). By doing so, it is also recast as a holistic process which provides the starting point for the leadership theory presented here.

Holistic Leadership Theory

Popper (2004) asserts that leadership is a relationship that extends beyond the properties of leaders and followers, because "the conceptualization of leadership as relationship permits an integrative view of leaders, followers, and circumstances, and thus reduces the bias . . . of giving too much weight to the leader" (p. 118). According to Popper, influence is a central feature of leadership and it arises from the emotive force that emanates from leadership relationships. It is this emotive force that creates the leadership mandate of charismatic leaders which has evolved into its operationalized and most researched form - transformational leadership.

In describing the three forms of relationship that leadership can produce, Popper (2004) noted that developmental relationships are characterized by the ability to create an environment of psychological safety that allows participants to engage in developmentally oriented behaviors including those most closely associated with transformational leadership - individualized consideration, autonomy reinforcement, and the promotion of trust, self-confidence, self-esteem and achievement orientation.

However, even this interpretation remains constrained by the very limitation that it exposes: that is, positioning the leader as the locus of causality in the leadership relationship. Popper (2004) hints at the solution by referring to the routinization of charisma, noting that this process breaks the bond between follower and a specific leader and converts it into a property of the institution or organization. Thus, the glaring conundrum in the leadership literature lies in how to successfully instigate this routinization process. Holistic leadership theory suggests that the answer lies in defining the unit of analysis not as the leader, the follower, the circumstance, or the relationship, but rather as a holistic system of development.

Holistic Development

Wapner and Demick (2003) maintain that holistic development is inherently systems-oriented and identify the "person-in-environment" as the system state. This interface is contextualized according to three dimensions that relate to both person and environment: the bio-physical, the psychosocial, and the sociocultural. A holistic system's features are interactionistic, involve a process of adaptation, reflect change as a feature of transformation, and require synchronization and coordination of its operating elements (Magnusson, 2001). From this perspective, leader, follower, and circumstance are not jockeying for a position of control but are instead discrete components of a series of interconnected systems that continuously "adapt, transform, coordinate and synchronize" with each other throughout the leadership process.

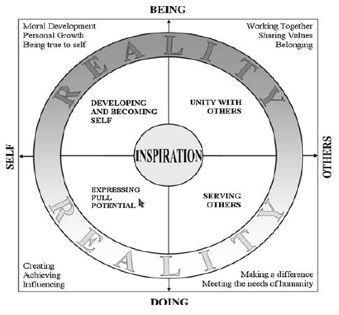

Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2009) add to this construct by emphasizing the role of meaningful work in framing the holistic development process, stating that "a sense of coherence and wholeness is particularly important in experiencing meaningfulness" (p.502). Based on research into the elements of meaningful work, they produced a model of holistic development comprised of four quadrants - developing and becoming self, unity with others, expressing full potentialand serving others - that, it can be argued, orient the person-in-environment system state. Popper (2004) also addresses the role of meaning in symbolic leadership relationships by highlighting the impact that leaders have on followers' self-concept and motivation for self-expression. Leaders in positions of formal authority have the opportunity to project values that followers can internalize as prized components of their self-concept and sources of motivation through linkages to an idealized vision articulated by the leader.

Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2009) add to this construct by emphasizing the role of meaningful work in framing the holistic development process, stating that "a sense of coherence and wholeness is particularly important in experiencing meaningfulness" (p.502). Based on research into the elements of meaningful work, they produced a model of holistic development comprised of four quadrants - developing and becoming self, unity with others, expressing full potentialand serving others - that, it can be argued, orient the person-in-environment system state. Popper (2004) also addresses the role of meaning in symbolic leadership relationships by highlighting the impact that leaders have on followers' self-concept and motivation for self-expression. Leaders in positions of formal authority have the opportunity to project values that followers can internalize as prized components of their self-concept and sources of motivation through linkages to an idealized vision articulated by the leader.Lips-Wiersma and Morris's (2009) theory of holistic development asserts that leadership does not, and in fact cannot, manufacture or manage meaning for others. It is instead challenged to find ways to promote the integration of self-defined meaningful purposes that emerge organically from the individual and are subsequently aligned with the broader goals and objectives of the organization. This view is embodied in the definition offered by Rogers, Mentkowski, and Hart (2006) in which holistic development is described as "a further integration of the meaning making self" (p.500).

In their investigation of the relationship between holistic development and performance, Rogers, Mentowski, and Hart (2006) conducted a meta-analytic review of research studies in support of their metatheory that "person in context" and intentional focus of meaning converge to create a framework for holistic development and performance. Their metatheory forms a matrix in which the structures of the person and external contextual frames such as the working environment intersect a plane of internal versus external foci of meaning. This matrix yields four domains of growth - reasoning, performance, self-reflection, and development. Several concepts emerged from their analysis that would be germane to an emerging theory of holistic leadership. When combined, these theories coalesce as a leadership imperative highlighting the need for:

- An assemblage of self-directed participants.

- Environments that promote the development of meta-cognitive skills like reflective thinking and pattern recognition to support the active use of mental models that will sustain constructive, autonomous decision-making.

- Leaders that engage participants in ways that demonstrate respect for the autonomy and individual capacities of their members.

- A collective approach to the development of member capacities in a way that seeds meaningfulness into the work environment.

These perspectives on holistic development map to elements of the leadership theories that have retained their salience and applicability over time. They include the relationship between leader personality traits and leadership performance; personal and organizational values and leadership behavior; leader influence and follower motivation; and follower motivation and organizational performance. Further, this convergence of holistic development and integrative approaches to leadership presage the type of learning organizations described by Senge (2006).In the opening pages of his book, Senge (2006) describes learning organizations as places "where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together" (p. 3). According to Senge, these organizations can be identified through the presence of five distinct disciplines:

- Systems Thinking - the ability to perceive complete patterns of interrelated events for purposes of producing more effective outcomes.

- Personal Mastery - the ability to harness, hone, and develop one's psychosocial capacity on an ongoing basis.

- Mental Models - the conscious and subconscious forms of mental imagery used to shape one's understanding of, and relationship to, his or her environment.

- Shared Vision - An ideal future state that is collectively prized and pursued as a goal.

- Team Learning - Engagement in collective dialogues that produce deeper insights than can be achieved individually.

The evolution of leadership theory as articulated above has, when joined with theories of adult holistic development, provided a kaleidoscopic image of the learning organization. The articulation of holistic leadership theory that follows seeks to bring that image into a more unified focus. Emerging from these precepts, holistic leadership is defined as a values-based approach to producing optimal outcomes through the collaborative development of all participants in the process, at all levels of functional performance.

Holistic Leadership Defined

The theory and resulting definition of holistic leadership presented here is not the first or only one attempted. On her website, Orlov (2003) describes holistic leadership as a methodology focusing on systemic development that impacts "oneself as leader, others as followers, and the environment" all resulting in "a journey that leads toward transformation at the individual, team, and organizational/community levels" (p. 1). Taggart (2009) offers a holistic leadership model on his website that he refers to as an "integrated approach to leadership." It includes components such as organizational teaching, personal mastery, reflection, inquiry, stewardship, visionary and strategic action, results orientation, thought leadership, power-sharing, collaboration, and nurturing. Similar to Orlov, Taggart's model also addresses a psycho-spiritual triad of personal wellness focused on mind, body, and spirit.

Tice (1993) describes holistic leadership as a people-centered approach that is both process and outcome oriented. Participants at all levels of the organization share responsibility for the activities that contribute to successful functioning and produce an environment where the organization serves more as an interactive and self-reinforcing community then a top-down hierarchical structure. These depictions of holistic leadership align with the prevailing research on adult holistic development which - when integrated with the integrative paradigm of leadership theories - transmute into the singular theory of holistic leadership presented here. A closer inspection of each element of the definition of holistic leadership will illustrate how.

A Values-Based Approach

Leadership ethics is the most readily identifiable example of a values-based approach to leadership. Ethics and moral orientations are values representations and have been directly linked with servant and values-based leadership styles (McCuddy, 2008). However, the very definition of a value suggests that a "values-based approach" can be broadly defined. In quoting Pearsall and Trumbell (2003), McCuddy describes values as those principles, standards, and judgments that one deems as significant or important. He proceeds to suggest that elevating standards on a personal level will not necessarily correlate with what is "good, right, fair and just" according to the standards of others. Thus, a values-based approach in this or any context must be explicitly defined.

The values-based approach of holistic leadership places equal emphasis on the welfare of the individual, the organization, and the larger community. This fragment of the holistic leadership definition finds initial affinity with the stewardship theory. Lussier and Achua (2007) define stewardship within a leadership context as "an employee-focused form of leadership that empowers followers to make decisions and have control over their jobs" (p.386). While this definition functions well as a description of the outcome of a values-based approach to leadership, it obscures the central function that stewardship actually plays in facilitating that outcome.

Stewardship is more appropriately described as the "wise use, development and appropriate conservation of resources that have been entrusted to the care of human beings" (McCuddy, 2008, p. 3). When combined, Lussier, Achua, and McCuddy's definitions translate into a value element dictating that holistic leadership must cultivate entrusted resources - both human and economic - in a way that supports growth, self-determination, and both individual and collective responsibility. Such a perspective also aligns with the four quadrants of Lips-Wiersma's and Morris's (2009) model -developing and becoming self, unity with others, expressing full potential, and serving others - which suggests that a values-based approach is likely to produce working environments that members find meaningful.

Figure 1: Chart model developed by Mariolein Lips-Wiersma & Lani Morris. (Reprinted with permission)

Servant leadership expands upon this value element by promoting self- transcendence in the service of supporting the growth and development of others (Lussier & Achua, 2007). Characteristics associated with servant leadership include stewardship, active listening, self-awareness, community building, and commitment to growth (McCuddy & Cavin, 2008). In addition, through their research into the relationship between servant leadership and leadership effectiveness, McCuddy and Cavin were able to link servant leadership with moral orientations. McCuddy's (2005) theory of fundamental moral orientation has three basic categories arranged on a continuum anchored by selfishness on one end, selflessness on the other, and self-fullness in the middle. The values element of holistic leadership aligns with self-fullness in several respects.

First, it accommodates the remaining fragments of the definition of holistic leadership, including the pursuit of optimal performance outcomes in a manner that is inconsistent with selfish goals and supportive of - though not necessarily requiring - selfless acts. Second, it frames leadership values as a balance between "reasonable self-interest and reasonable concern for the common good" (McCuddy, 2008, p 3). Third, it contextualizes values-based leadership theories like authentic and level three leadership which both focus on the moral orientations and behaviors of the leader. Accordingly, a values-based approach serves as a precursor that supports and validates the four remaining components of holistic leadership. Namely, it establishes the collective development of all participants in the leadership process as a central principle that will guide future behavior and decision-making.

Producing Optimal Outcomes

A leadership model that does not address performance outcomes has limited utility in practice. The goal of any leadership effort is to direct behavior towards a desired goal. As with other integrative leadership theories, a basic premise of holistic leadership is that it actually supports the achievement of the most desirable outcomes for the leadership unit (organization, group, or individual). The current focus on transformational leadership has produced consistent empirical support for connections between it and team learning and effectiveness (Chiu, Lin, & Chen, 2009), commitment to organizational change (Herold, Fedor, Caldwell & Liu, 2008; Howarth & Rafferty, 2009), job performance (Chung-Kai & Chia-Hung, 2009), and leader effectiveness (Barroso Castro, Villegas Periñan, & Casillas Bueno, 2008; Resick, Whitman, Weingarden & Hiller, 2009). The mediating effects attributable to transformational leadership represent core elements of holistic leadership theory.

For example, team-based work produces optimal outcomes because it capitalizes upon the collective strengths of team members while redistributing weaknesses so that they can be absorbed and compensated for by the group. Existing literature on the conditions that promote team effectiveness emphasize the interdependence of both members and tasks, the emergence of shared mental models, and an enabling structure that provides psychological safety for team members (Burke, Stagl, Salas, Pierce & Kendall, 2006). These correlations form the basis for asserting that the collaborative development of all participants in the leadership process will produce the types of psychological climates that facilitate optimal outcomes.

Transformational leadership has been empirically linked with team effectiveness in part because of its role in facilitating team learning behavior and a team learning orientation that in turn supports team behavioral integration in ways consistent with the findings described in the Burke et al., (2006) study (Chiu, Lin, & Chien, 2009). Accordingly, the residual effects of the transformational leader's attention to the specific needs and concerns of individual members - even within a team setting - appear to translate into an increased commitment to the goals of the organizational unit. Likewise, holistic leadership practice leverages these same attributes by inculcating them as leadership values.

Researchers also found a correlation between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy that was empirically linked not only to an improvement in job performance ratings but objective performance standards like increased sales (Gong, Huang & Farh, 2009). In that study, transformational leadership and learning orientation were associated as predictors of creative self-efficacy. Similar research on transformational leadership and social exchange theory attribute these connections to the increase in trust and loyalty to leader that transformational leaders engender. Based on this research, it is reasonable to expect holistic leadership practices to produce environments of increased trust and loyalty that extend beyond specific leaders to the collective leadership enterprise.

Researchers also found a correlation between transformational leadership and creative self-efficacy that was empirically linked not only to an improvement in job performance ratings but objective performance standards like increased sales (Gong, Huang & Farh, 2009). In that study, transformational leadership and learning orientation were associated as predictors of creative self-efficacy. Similar research on transformational leadership and social exchange theory attribute these connections to the increase in trust and loyalty to leader that transformational leaders engender. Based on this research, it is reasonable to expect holistic leadership practices to produce environments of increased trust and loyalty that extend beyond specific leaders to the collective leadership enterprise.This set of leadership literature suggests that integrative models engage participants in ways that inspire trust because they demonstrate a commitment to the welfare of the individual. In turn, the individual is inspired to commit to the values of the leadership unit which includes the success of organizational goals and objectives. Thus, we can conclude that a values-based approach to leadership that evidences support for the collaborative development and continuing well-being of participating members should produce better outcomes. The next element of holistic leadership must then specifically address how to demonstrate a commitment to the welfare of individual members through their collaborative development.

Collaborative Development

Individuals who are brought together by the pursuit of the same or similarly aligned goals represent a unique collective unit. Organizations accomplish their goals through the efforts of their members. Transformational, participatory, and other empowering approaches to leadership link successful outcomes to the ability to encourage employees to align personal achievement goals to organizational goals. Transformational leadership as the most widely researched of the integrative theories, suggests that this link is accomplished through the inspirational vision and idealized influence of the leader. Participatory leadership styles rely on social exchange theory by promoting the involvement of members in exchange for a commitment to advance organizational goals. Holistic leadership extends these approaches by explicitly predicating success in achieving organizational objectives on the personal and professional development of participating members.

By shifting the focus from the charismatic capabilities of a transformational leader to the ongoing relationship between individual members and the organization, holistic leadership offers a more stable and transferrable structure upon which to establish personal and organizational goal alignment. There are at least two residual benefits to this approach. First, individual members of the organization no longer need to experience personal achievement vicariously through the articulated vision of the leader but are instead facilitated in making a direct connection between their efforts and the organization's success. And second, leaders are released "from the burden of creating and carrying the ‘meaning' of work and organization" (Lips-Weirsma & Morris, 2009, p. 505). Moreover, the notion of pursuing goal achievement collaboratively is at the heart of the servant leader model.

In articulating Greenleaf's servant leadership model, Daft (2008) lists four basic precepts: (1) put service before self-interest; (2) listen first to affirm others; (3) inspire trust by being trustworthy and; (4) nourish others to help them become whole. It is the fourth of these precepts that speaks specifically to the collaborative development element of holistic leadership while aligning it with holistic development models like the one offered by Lips-Wiersma and Morris (2009). A holistic approach is motivated by more than improved organizational performance. It is committed to the personal and professional growth of participating members, ostensibly putting the former before the latter.

This element is not necessarily a prerequisite of participatory models but is nonetheless compatible with them because it anticipates variability in the capacity of organization members and commits to bringing developmental opportunities to them wherever they are in their growth process. Contingency theories suggest that participation must be limited by developmental level, situational urgency, and the environmental structure in which members operate (Houghton & Yoho, 2005). However, holistic leadership takes a contrary position. Rather than limiting participation based on these contingencies, participants should be developed so that they will be capable of responding appropriately to the tasks or situations that may confront them. Consequently, each member's personal commitment to the organization's success is more firmly rooted because of the organization's demonstrated commitment to each member's personal success. Collaborative development is achieved because the organization's approach is to develop itself and its members together.

All Participants in the Process

To be effective, collaborative development must take the individual capacities of organization members into account. True empowerment and participation provides choice in the form of opportunities to:

- Exercise self-determination;

- Find meaning in one's work;

- Develop self-efficacy; and

- See the impact of one's contributions to the organization's objectives (Houghton & Yoho, 2005).

Holistic leadership theory rests on the central premise that it is only through the opportunity to exercise self-determination that one can find meaning in one's work, develop self-efficacy, and see the impact of his or her contributions to the organization's objectives. Therefore, for individualized consideration to result in member empowerment, it must be embedded in institutionalized structures that position all participants in the leadership process closer to the right on the self-determination continuum developed by Ryan and Deci (2000).

The Importance of Self-Determination

According to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), the presence or absence of self-determination is a composite of motivational tendencies, self-regulatory style, perceived locus of causality, and the dominant regulatory processes employed by the individual (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Each member of the leadership process - regardless of formal position - brings with them their current motivational tendencies, which range from amotivation at the left most end of the continuum through extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. Each motivational tendency is coupled with a corresponding self-regulatory style. While the first two elements of self- determination reside within the constitution of the individual, collaborative development has the potential to influence the perceived locus of causality and the dominant regulatory processes by shifting actual decision-making to the participant wherever possible and anchoring those decisions in pro-social values that support the meaning-making experience in a positive way.

As participants are regularly afforded opportunities to engage in autonomous decision-making, the perceived locus of causality shifts from the impersonal or external on the left most end of the continuum towards an internal locus of causality resulting from repeated opportunities to direct ones' own activities. Similarly, the least determined regulatory processes are described by Ryan and Deci (2000) as non-intentional, non-valuing, incompetence and loss of control. However, actively engaging participants in decision-making processes that relate to their work and supporting their evolving mastery as autonomous decision-makers causes their efforts to become intentional and their contributions to be perceived as valued. They now acquire control and experience-increased feelings of competence. These experiences would be expected to move their dominant regulatory processes to the right, engendering increased interest, enjoyment, and inherent satisfaction.

Houghton and Yoho (2005) cite as a limitation of fully participatory decision-making, the cost of investment when weighed against the potential returns for certain classes of employees (e.g., temporary workers). However, there is no way to avoid the fact that this is a values proposition. When decision-making opportunities are offered to some members but not others, existing power disparities are exacerbated and can only undermine even the best intentions for member involvement.

Social exchange-based theories of leadership rest on perceptions of equity and justice. Further, member perceptions of justice and dignity in the conditions of employment are found to be inextricably linked to the ability to find meaningfulness in their work (Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009). When members are afforded opportunities to participate in the decisions that affect them, not only does that contribute to increased feelings of meaningfulness, it engenders a level of trust in their organizations that promotes member commitment to the achievement of an organization's goals. This approach also demonstrates the individualized consideration identified with transformational leadership and helps to routinize it by conveying the residual goodwill from the individual leader to the organization as a whole, as Popper (2004) recommends.

Individually-focused developmental activities also build the functional capacity of the organization by extending the range of talent and expertise available internally. This is an indispensible requirement of any participatory approach that seeks to respond to the inherent vulnerabilities highlighted by situational theories. For all members to have greater access to participation in the conditions of their engagement with an organization, all members must have access to developmental opportunities that will enable them to participate competently and effectively. It is the principle of participant development as a requisite element of leadership practice that distinguishes holistic leadership theory from its paradigmatic counterparts.

All Levels of Functional Performance

The definition of holistic leadership theory presented here infers the demonstration of a commensurate level of leadership on the part of all participants in the leadership process. Consequently, functional performance emerges as a primary concern that must be further segmented into two categories - functional leveland level of function.

Functional level

The multidirectional and interdependent nature of holistic leadership suggests that it is unilaterally applicable across a range of settings and contexts. To be practical, however, this premise requires a unifying construct that is described here as the leadership unit. The leadership unit, for purposes of this theory, is deemed to exist in one of four forms that often operate simultaneously. They are:

- The I unit - representing the individual at the intra-psychic level of functioning.

- The "Dy" unit - representing any dyad of two individuals and corresponding to a meso-level class of functioning.

- The Team unit - defined here as consisting of not less than three and not more than seven members,1corresponding with a micro-level of functioning.

- The "Weam" unit - reserved for groups of eight or more individuals, including collections of teams and dyads, organizations, communities, and societies — also representing the macro and meta levels of functioning.

The dictates of holistic leadership apply to any and all leadership units individually and collectively with the understanding that all leadership units are ultimately a collection of "I" units. Therefore, all levels of functional performance as the phrase resides within the complete definition of holistic leadership theory, refer first to the individual capacity to perform as a member in different leadership units. Thereafter, as those leadership units self-organize or are organized externally, holistic leadership theory dictates how Weam (and some team) level leadership units function when formally structured.Levels of function

Holistic leadership does not conflict with existing hierarchical structures. Rather, it recognizes that collaborative development within a Weam context (i.e., an organizational setting) is best supported within a stable structure so that development at the I-unit level can occur in place. In addition, every type of leadership unit within a Weam context must be able to associate the responsibilities of its assigned function(s) with the broader mission if the mission, vision and values are to be internalized for consistent practice by constituent members. A clearly identifiable structure supports this requirement.

For development of all members of a Weam to occur in place, more experienced members must be appropriately positioned to facilitate and support the development of less experienced members. Thus, holistic leadership also recognizes that development occurs in successive stages or levels of function. The formally designated structure of these stages is of less consequence than the levels of performance that must be represented. Accordingly, holistic leadership theory posits four distinct levels of functional performance at the Weam level: (1) executive, (2) managerial, (3) supervisory; and (4) frontline.

The executive level is responsible for creating and maintaining a climate hospitable to holistic leadership principles. Executive level commitment is a prerequisite for the successful implementation of holistic leadership practices throughout any collective enterprise. Referring once again to Popper's (2004) characterization of leadership as relationship, the influence of this leadership unit is on the moral or values level of development. The charismatic content of the leadership relationship can only be successfully routinized if a collective identity exists through which values are transmitted so that individual members can identify and internalize them for meaning-making purposes. This includes the utilization of constructive mental models. The managerial level then translates these values into an organizational structure with supporting policies and procedures. This level is distinguished from the supervisory level by the latter's function as the direct and proximal reinforcement of holistic leadership practices along with the modeling of those behaviors for the frontline level. As Popper (2004) notes, developmental interactions require close interpersonal contact. It is only through these one-on-one interactions that the prerequisite developmental conditions of psychological safety and trust can emerge.

In this respect, the supervisory and managerial leadership units serve critical functions. The supervisory level underscores that all leadership relationships in a holistic leadership framework have a supervisory component that will either undermine or reinforce the salience of holistic leadership principles by virtue of the extent to which supportive psychological climates are established and maintained. The managerial level of function serves as the conduit through which individual psychological climates become organizational climates.

Finally, it is the frontline level whose practice directly impacts upon how different leadership units are experienced by those on the outside and thus validates the extent to which holistic leadership practices are fully functional within a collective setting (e.g., an organization). SDT reminds us that human potential is realized when the three basic needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness are met (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Frontline level leadership represents the proving ground for whether the prevailing leadership structure meets these needs. Through its emphasis on the collective development of all participants in the process, holistic leadership theory offers a means to do so.

The four levels of functional performance are applicable to Weam units of all sizes. Smaller settings not able to support four levels of supervision will nonetheless need to perform all four levels of function even if those functions are collapsed into fewer hierarchical levels or formal titles. For example, a small nonprofit organization with a limited number of employees must still establish the values for the organization (executive), an organizational structure for their implementation (managerial), mechanisms for supporting their consistent practice (supervisory) and the unfailing fulfillment of those practices with all external participants (frontline).

Implications for Leader, Leadership, and Organizational Development

The primary implication of holistic leadership theory as it is presented here lies in its connections between the development of the leader, follower, and circumstance and the interactions that recast leadership as a holistic process (i.e., a function of systems-oriented processes, interacting with and adapting to one another). These processes are theorized to produce the best outcomes when focused on a values-based approach to the collaborative development of all participating members. This view of leadership is implicit in several leadership theories already identified as having informed holistic leadership theory - namely transformational, servant, stewardship, authentic, and level three leadership. However, each of these leadership theories rests authority and responsibility with the titular leader as the arbiter and primary instigator of those philosophies in practice. As a consequence, the outcomes even in the most participation-oriented environments become leader dependent. Holistic leadership theory mediates this limitation.

With holistic leadership, a baseline level of leadership behavior (e.g., self-leadership) is expected and developed from within every participant in the leadership enterprise. This view leads to a more authentic expression of participant empowerment because responsibility is shared rather than conferred. Treating all participants as leaders supports the concept of leaders as partners in the leadership process. Thus, as the traditional leadership profile is transformed, the holistic leader becomes more adjuvant than advocate.

The emphasis on collaborative development as a parallel pursuit with goal attainment comes closer to realizing the aspiration of full participation by organization members than has been realistically articulated by other leadership models. In the present theory, each member of a leadership endeavor is viewed as a full - albeit developing - partner in the process. The enterprise itself serves as both structure and catalyst for the emergence of self-leadership qualities through self-determined activities that allow each member to develop his or her relative capacity to contribute. The leadership hierarchy is then more accurately viewed as a measure of the ability to facilitate growth in self and others, with organizational outcomes serving as external referents for success.

One of the most important facets of these leadership interactions relates to mental models. Mental models are the cognitive processes that shape perceptions of external reality and our personal responses to it. They shape the VABES that Clawson (2009) attributes to leadership performance and are identified as one of the five components of Senge's (2006) model of a learning organization. More importantly, they exist for every member of an organization, regardless of position and thus represent a singular predictor of organizational performance. Holistic leadership theory's potential for the development of the leader, the led, and the organization lies in its ability to influence the mental models of organizational members in a more positive and productive manner.

The lessons learned from overcoming challenges and obstacles have been deemed more instrumental to leadership development than formal training by those who have experienced both (Johnson, 2008). The underlying premise of holistic leadership theory is that the outcomes of effective leadership result from the alignment of values and resulting behaviors between the organization and its members. This is combined with a commitment to the development of all participants concomitant with the pursuit of organizational goals. This approach produces a climate where the pursuit of meaningful purposes can emerge organically, which is consistent with what holistic development reports as the primary motive goal for all human beings. In the process, self-leadership capacity is expanded through the exercise of self-determined activities as participants respond to the challenges and obstacles faced during the ongoing performance of their professional responsibilities.

As a legacy of both transformational leadership and other participatory leadership models, holistic leadership uses the Weam unit (e.g., the organization, community group, agency) to develop self-leaders throughout any collective enterprise by linking task, personal and professional performance, opportunities for self-determination, and expectations for success. As a consequence, organizational development and individual development - at all levels of the organization - become structurally entwined.

The tacit messages that are imparted through the practice of a values-based approach to collaborative development are expected to produce optimal outcomes when adopted as a leadership philosophy within a Weam setting. The mental models that such a philosophy fosters include a belief in the worth of all participants and the value of their contributions, the importance of collaborative approaches to goal attainment, and confidence in the abilities of all leadership units - including I units - to accomplish goals. As these mental models continue to be supported through policy and practice, they are internalized in ways that promote the behaviors highlighted by integrative leadership theories and that result in desired outcomes. Members are inspired, motivated, and committed to the achievement of individual and collective goals.

As mentioned previously, Senge (2006) predicts such an outcome in his description of the five characteristics of a learning organization. As presented here, holistic leadership supports systems thinking and team learning by virtue of its emphasis on collaborative development; facilitates personal mastery through the development of all participants; produces the types of mental models that generate desired outcomes; and ultimately positions the organization to build a shared vision for the organization's success because the vision is linked to the individual successes of its members, thereby facilitating a sense of meaningfulness in work that is authentic and intrinsically motivating.

Present Limitations and Future Research

The viability of any theory depends upon the extent to which its claims can be validated through empirical investigation. One limitation of holistic leadership theory is that it is based upon a number of assumptions that have yet to be proven. Future research validating correlations between holistic leadership and self-leadership and holistic leadership and the positive outcomes associated with transformational leadership would be useful in this regard. However, holistic leadership theory must first be cast in the form of a testable model of leadership. Such a model 2 has been developed by the author and contains the following salient features based on the theory articulated above:

- A framework of thirty-one leadership competencies that support the practice of holistic values and collaborative development strategies in organized settings; and

- Use of the four levels of functional performance as an organizing framework that produces leadership scaffolds to support the development of self-leadership capacity while preparing participating members for the exercise of increasing levels of self-determination and participatory decision-making.

The current conceptualization of holistic leadership serves as the theoretical underpinning for the above-referenced model. The model can then be used to assess organizational climate as well as individual readiness to adopt the kind of practices that produce learning organizations and empowered participants. More importantly, the theory and corresponding model offer concrete strategies for producing the aforementioned results — something that continues to be needed by leadership practitioners.

The promise of holistic leadership theory lies in its use as a tool for the development of leadership units of all sizes including Weam level settings that support the dissemination and practice of holistic leadership principles. Organizational culture and climate research would be an appropriate avenue of investigation for this aspect of the theory and could be validated by measuring the influence of holistic leadership practices (i.e., through application of the Holistic Leadership Competency Model) on performance outcomes.

Holistic leadership theory codifies the best of what has emerged from the holistic development and integrative class of leadership theories and synthesizes them into a singular framework that supports further research and refinement. This theory's delineation as presented here, is intended as a first step in that direction. Its propositions are anchored in the wealth of leadership and developmental scholarship that has preceded it and that now stands ready for its next iteration.

References

Barroso Castro, C., Villegas Perinan, M. M., & Casillas Bueno, J. C. (2008). Transformational leadership and followers' attitudes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(10), 1842-1863. doi:10.1080/09585190802324601.

Bass, B. & Bass, R. (2008). The bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research h and managerial application (4th ed.) Free Press.

Burke, C. S., Stagl, K. C., Salas, E., Pierce, L., & Kendall, D. (2006). Understanding team adaptation: A conceptual analysis and model. Journal of Applied Psychology,91(6),1189-1207. doi:10.1037/0021 -9010.91.6.1189.

Chemers, M. M. (2000). Leadership research and theory: A functional integration. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4, 27-43. doi:10.1037/1089-2699.4.1.27.

Chiu, C., Lin, H., & Chien, S. (2009). Transformational leadership and team behavioral integration: The mediating role of team learning. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1-6.

Chung-Kai, L. I., & Chia-Hung, H. (2009). The influence of transformational leadership on workplace relationships and job performance. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 37, 1129-1142. doi:10.2224/sbp.2009.37.8.1129.

Clawson, J. G. (2009). Level three leadership: Getting below the surface (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Daft, R. L. (2008). The leadership experience (4th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Houghton, J. D., & Yoho, S. K. (2005). Toward a contingency model of leadership and psychological empowerment: When should self-leadership be encouraged? Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11, 65-83. doi:10.1177/107179190501100406.

Howarth, M. D., & Rafferty, A. E. (2009). Transformational leadership and organizational change: The impact of vision content and delivery. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1-6.

Johnson, H. H. (2008). Mental models and transformative learning: The key to leadership development? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19, 85-89. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1227.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2000). Five-factor model of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 751-765. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.751.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lips-Wiersma, M., & Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between meaningful work and the management of meaning. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 491-511. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0118-0.

Lussier, R. N., & Achua, C. F. (2007). Leadership: Theory, application, & skill development (3rd ed.). Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning.

McCuddy, M. K. (2005). Linking moral alternatives and stewardship options to personal and organizational outcomes: A proposed model. Review of Business Research, 5, 141-146.

McCuddy, M. K. (2008). Fundamental moral orientations: Implications for values based leadership. Retrieved May 21, 2010, from http://www.valuesbasedleadershipjournal.com/issues/vol1issue1/mccuddy.php.

McCuddy, M. K., & Cavin, M. C. (2008). Fundamental moral orientations, servant leadership and leadership effectiveness: An empirical test. Review of Business Research, 8, 107-117.

Nahavandi, A. (2009). The art and science of leadership (5th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Orlov, J. (2003). The holistic leader: A developmental systemtic approach to leadership. Retrieved Mar. 3, 2010, from http://www.julieorlov.com/docs/holistic_leader_article.pdf.

Pearce, C. L., Sims Jr., H. P., Cox, J. F., Ball, G., Schnell, E., Smith, K. A., & Trevino, L. (2003). Transactors, transformers and beyond: A multi-method development of theoretical typology of leadership. The Journal of Management Development, 22, 273-307. doi:10.1108/02621710310467587.

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 327-340.

Popper, M. (2004). Leadership as relationship. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 34, 107-125. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8308.2004.00238.x.

Resick, C. J., Whitman, D. S., Weingarden, S. M., & Hiller, N. J. (2009). The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: Examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1365-1381. doi:10.1037/a0016238.

Rogers, G., Mentkowski, M., & Hart, J. R. (2006). Adult holistic development and multidimensional performance. In C. H. Hoare (Ed.), Handbook of adult development and learning (pp. 498-534). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55,68-78. doi:10.1037/0003-66X. 55 .1 .68.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Sharma, M., & Ghosh, A. (2007). Does team size matter? A study of the impact of team size on the transactive memory system and performance of IT sector teams. South Asian Journal of Manage-ment, 14, 96-115.

Taggart, J. L. (2009). Holistic leadership. Retrieved March 3, 2010, from http://www.leadershipworld connect.com/holistic.pdf.

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Oke, A. (2010). Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investtigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 517-529. doi:10.1037/a0018867.

Wapner, S. & Demick, J. (2003). Adult development:The holistic, developmental, and systems-oriented perspective. In J. Demick, & C. Andreoletti (Eds.), Handbook of adult development (pp. 63-83). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Author Biography

Dr. K. Candis Best is an educator, consultant, speaker, and author. In May of 2008, she made her literary debut with Leaving Legacies: Reflections from the Prickly Path to Leadership, an entertaining and moving account of her eleven-year odyssey as a public health executive that was recognized by USA Book News as one of the best books of 2008.

Before embarking upon a successful career in public health administration, Candis worked as an attorney in private practice. She is licensed to practice in the States of New York and New Jersey as well as before the federal courts of the Eastern District of New York. In addition to a law degree from Villanova University, she possesses a Masters in Business Administration from Adelphi University, a Masters in Psychology from Capella University, and a Ph.D. in Social Welfare Research and Policy Development from Stony Brook University on Long Island, where she enjoyed the distinction of being a W. Burghardt Turner Fellow. She holds board certifications in Healthcare Management and as a Human Services Practitioner and is a fellow of the American College of Healthcare Executives.

Candis has served as a professor of law, business, research, and public health courses at the undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels. Her volunteer activities have included serving on the boards of a variety of philanthropic institutions as well as serving as a volunteer arbitrator for small claims court. A native New Yorker, Candis resides in the Clinton Hill section of Brooklyn.

1 The upper limit of seven was selected based on a study that suggested the optimal team size is between five and seven members (Sharma & Ghosh, 2007).

2 For more information on the Holistic Leadership Competency Model, contact the author.