- CONTENTS:

- Letter from the EditorArticle SummariesDedication and RemembranceEmploying the Seven Army Values to Win Hearts and MindsCommentary: The Business of Warfare: "Winning Hearts and Minds"Conflict Resolution: Cultural Understanding ImperativeThe Personal Values of School Leaders in Pakistan: A Contextual Model of Regulation and InfluenceThe Needs of the Stakeholders are the Seeds of Growth for the Organisation: Vignettes of Wisdom from Mr. G. NarayanaThe Character X Factor in Selecting Leaders: Beyond ethics, virtues, and valuesA Model for Implementing a Successful Sustainability StrategyEngaged Leadership: New Concept or Evolutionary in Nature?

- THE PERSONAL VALUES OF SCHOOL LEADERS IN PAKISTAN: A CONTEXTUAL MODEL OF REGULATION AND INFLUENCE

“Values are those conceptions of the desirable which motivate individuals and collective groups to act in particular ways to achieve particular ends. They reflect an individual’s basic motivations, and shape the attitudes and reveal the intention behind actions.”

— P.T. Begley

SHARIFULLAH BAIG, FACULTY MEMBER

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT CENTRE NORTH

INSTITUTE FOR EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

AGA KHAN UNIVERSITY, PAKISTANAbstract

This paper illuminates the sources of personal values and their influence on the leadership practices of two school head teachers in the particular context of Pakistan. A comparative case study method has been followed within the qualitative research paradigm where semi-structured interviews, observations, and document analyses were used as the main data collection tools. This study finds that the types of personal values and the motivational bases for the acquisition of such values are very much contextually-centered. The data for both principals, despite the exceedingly different characteristics of their childhood communities, reveals that the inherent religious and communal values of their divergent communities remain a strong motivational base for each head teacher. Their leadership practices are considerably influenced by their personal values in terms of cultivating a school culture, establishing structures, and fostering relationships with the external community. Based on the study’s findings, a contextualized model has been proposed.

Introduction

The all-embracing involvement of head teachers in the technical, social, and moral aspects of school life is exerting enormous pressure on their time and energies as leaders. Johnson, MacCreery and Castelli (2000) maintain that, "Headship can clearly be seen not as some technical exercise but as being about social, moral, and educational values and their playing out in action" (p.400). In this complex arena of social, moral, and educational values, these head teachers are extensively involved in decision-making and problem-solving which eventually engage them in a continuous process of selecting preferred alternatives and rejecting others. During this process of selection and rejection of alternatives, they are mostly dealing with values involved in the social environment of the school. In this sense, the schools are value-laden rather than value-saturated places in which school leaders are exceedingly involved in tackling and grappling with various forms of values.

Furthermore, the rapid modernity and cultural globalization has additionally intensified and deepened the involvement of values and values-based conflicts among the stakeholders in a school milieu. The increasing diversity and pluralism in different societies has raised the number of competing values and value-laden conflicts. Explaining this kind of situation, Begley (2002) maintains that, "One very obvious outcome is the increase in the value conflicts that occur in school environments" (p.49). These value-laden conflicts are growing more frequently and becoming more complex among the stakeholders of the school. The nature of such emerging conflicts can be of different types. It may arise as an outcome of the interaction between two or more stakeholders of the school. Values-based conflicts can appear in different forms: personal, professional, and organizational. Any stakeholder of the school can develop a personal value repertoire contradictory to that of the organizational value structure.

This situation offers a challenging and complex scenario to the educational leaders of the school in terms of dealing with a variety of competing values, value-laden conflicts, and a range of value orientations. As captain of the ship, the head teacher has to accommodate the variety of values and stabilize the value-saturated complex environment of a school in order to ensure maximum effectiveness and efficiency. Dealing with the values and value-laden conflicts of the other stakeholders, the important aspects of head teacher‘s own personal values come into play. Law, Walker, and Dimmock (2003) maintain that, "Values act as powerful motivators or filters, which predispose principals toward seeing situations in certain ways and taking certain courses of actions" (p.505). Similarly, Hodgkinson (1999) argues, "In an important sense the leader just is a historically unique complex of values. And this value orientation affects everything" (p. xii). In exercising leadership duties, head teachers normally aspire to see things happening in accordance with their own personal values resulting in the formation of a distinctive school culture. The personal values of head teachers play a critical role in balancing and moderating all the other kind of values in the school milieu. Hence, these personal values intentionally or unintentionally influence the leadership practices of the head teachers. Therefore, deeming schools as value-laden or even value-saturated places, this study intended to explore the influence of personal values of the head teachers on their leadership practices in the context of two private secondary schools in Karachi, Pakistan.

Literature Review

With respect to school leadership literature, there is a growing tendency to use the words "ethics" and "morals" synonymously with values-related concepts (Sergiovanni, 1992). Other scholars, including Leonard (1999), Begley (2001), and Hodgkinson (1978), reserve the terms "ethics" and "principles" for a particular category of trans-rational values, while they use the word "values" as an all-encompassing term for all forms of the desirable. In the view of Willower (1999), "The study of values traditionally has dealt with what is good or desirable with the kind of behaviour that one should engage in to be virtuous" (p.121). Correspondingly, Begley (1999) maintains that, "Values are those conceptions of the desirable which motivate individuals and collective groups to act in particular ways to achieve particular ends. They reflect an individual‘s basic motivations, and shape the attitudes and reveal the intention behind actions" (p. 237). However, Parsons and Shils, as cited in Begley (1999), have provided a more comprehensive and concise definition. Accordingly, values are: "Conceptions explicit or implicit distinctive of any individual or characteristic of a group of the desirable which influences the selection from available modes, means and ends of action" (p.240).

Values and Educational Leadership

It is often believed that the culture of any school starts with the values and beliefs of the head teachers who seek to promote them among their school staff and students. Hicks (2003) argues that, "All employees bring some set of values and some wider world view with them when they enter the work place" (p.107). Therefore, as employees, head teachers also bring in their personal values and world views to the school. In this connection, Begley (2001) maintains that, "All leaders consciously or unconsciously employ values as guides in interpreting situations and suggesting appropriate administrative action. This is the artistry of leadership" (p.364). The studies in the developing societies have also confirmed the interconnectivity of school leadership and values. For example, Khaki (2005) maintains, "The heads‘ histories, beliefs and values influence how the heads exercise their management and leadership role. These factors provide a background to which the heads refer when explaining why they do certain things, the way they do" (p. 227). Russell (2001) reviewed the important literature about personal values. He maintained that values significantly impact leadership by affecting moral reasoning, behaviour, and leadership style. Values profoundly influence personal and organizational decision-making and the values of the leaders ultimately permeate the organizations they lead. He further maintains that leaders primarily shape the cultures of their organizations through modeling important values. Ultimately, values serve as the foundational essence of leadership.

Leithwood and Steinbach (1991, 1993) stress that values influence the problem-solving process both directly and indirectly. In direct influence, values act as preferences and dictate the school leaders‘ actions. With respect to indirect influence, values act as filters for determining the saliency of external factors in problem-solving. Likewise, Campbell, Gold, and Lunt (2003) explored that in different ways, the school leaders suggest that the ethnic, religious, and socio-economic characteristics of the local communities influence processes and practices within the school. They also explored that the school leader‘s values often involve attempts to change values and practices in the community rather than mirror or reinforce community values. These leaders aspire and try to articulate their values and discuss them with their staff and expect them to follow and in return, they are highly valued by the school leaders.

Similarly, Gurr, Drysdale, and Mulford (2006) explain that successful school leaders promote a culture of collegiality, collaboration, support, and trust and that this culture was firmly rooted in their democratic and social justice values and beliefs. Also, Gold, Evans, Earley, Halpin, and Collarbone (2003) conducted a study to explore how the "outstanding" principals translate their educational values into management and leadership practices. It explored that their leadership was clearly values-driven. The study provides insights into how some of these values and beliefs were demonstrated through the words and deeds of the school leaders.

In the Asian context, Law, Walker, and Dimmock (2003) conducted a study in the Protestant secondary school of Hong Kong. This research study focused on the principals‘ values and their impact on the principals‘ perceptions and management of problems. This study reveals that the links between values and problems are influenced by personal and organizational characteristics. Personal characteristics include the principal‘s age, gender, experiences, and strength of religious beliefs. Thus, organizational characteristics include the school‘s religious atmosphere and history, as well as the values shared by staff and principals and their autonomy to influence.

Methodology

The qualitative approach has been employed in this study to obtain in-depth and descriptive data about the personal values of the head teachers in the natural setting of their respective schools. Within the qualitative research paradigm, the comparative case study method was adopted in this research. Bogdan and Biklen (1998) state that, "…researchers do comparative studies; two or more case studies are done and then compared and contrasted" (p.62). In order to attain more breadth and depth, this research study is comprised of two case studies which focus on the head teachers of two different schools. After thoroughly analysing the individual cases, this study presents a comparative analytical view. Yin (2003) supports that analytic conclusion independently arising from two cases will be more powerful than those coming from a single case. Therefore, this research adopts this dual, comparative case study approach.

Two community-based high schools were selected as the research sites and their head teachers as the research participants in the cosmopolitan city of Karachi, Pakistan. The rationale behind pursuing the community-based secondary schools stemmed from their passion for serving their community and upholding particular values all of which could potentially provide rich data about values, the valuation process, and sources of values (Johnson, McCreery, and Castelli, 2000). Secondly, the principals of community-based, private secondary schools have greater powers and influence in their school affairs. Simkins, Sisum, and Memon (2003) maintain that, "Non- government heads generally had considerable powers over the management of staffing (including appointment, discipline, and in some cases, pay) and finance; whereas, the government heads had no such powers" (p.280). Hence, a greater level of power and influence may provide greater autonomy and opportunity to the principals for articulating and explicating their personal values.

This study employed semi-structured interviews and observations as the main tools for data collection. In order to ensure that the interviews were exclusively collecting the perspectives of the research participants, this study employed a four-round, specifically designed set of semi- structured interviews. The first round of the interview was more of an open conversation intended to understand their personal backgrounds, to assess their respective motivation levels, and generally to develop rapport. During the second phase, principals were asked to articulate the achievements and accomplishments in which they took pride. During the third round, both principals were asked to describe the most challenging dilemmas they had encountered during their professional careers and ultimately, the manners and tools they used to resolve same. They had further been asked to articulate some of the frequent problems experienced. The fourth and final rounds of interviews were mainly focused on the relationships that the principals forged with their students, teachers, and the wider parent community.

Gray (2004) maintains that, "Observation involves the systematic viewing of people‘s actions and the recording, analysis and interpretation of their behaviour"(p.239). In this regard, the organizational culture of the school, i.e., the nature of the relationships, the norms of practices, and the characteristics of the interactions among people with special reference to their relations and connections with the head teacher, delineated essential areas for observations. The quotes on the walls, the context of the paintings, the notices on the display boards, and the individual dress codes were all of critical importance. Observation and semi-structured interviews mutually enriched the data generated. At times, the observations provided useful insight needed to formulate additional questions during the semi-structured interviews while simultaneously some of the interview responses guided further observations.

This study was influenced by the grounded theory approach by reading and re-reading the data to extract themes (Merriam, 1998) for data analysis. The process of organizing, general sense making, coding, drawing themes, and finally interpreting the collected data (Cresswell, 2003) was employed in this study.

The research participants were informed about the nature, purpose, time, method, and the possible risks involved in the study. Secondly, the participants had been selected with their voluntary consent for participating in the study. The research participants enjoyed the right to withdraw from the study at any time if so desired. Furthermore, participants were permitted to review the interview transcripts for any clarification or adjustments which they believed deviated from their views as originally expressed. In order to maintain confidentiality, pseudonyms for the research participants and their respective institutions were used.

Discussion and Findings

“The Blessing School” and “Mr. Barkat”

The Blessing School, established in 2001, is a community-based institution aimed at providing quality education to the children of that particular community. The school started its journey from pre-primary and is now a secondary school, under the supervision of a board of trustees. Currently, there are 15 staff members including teaching staff and non-teaching staff serving 482 students from pre-primary to secondary classes. Mr. Barkat, my research participant, is its principal.

As an orphaned child, Mr. Barkat gained his initial education in his community-based orphanage, consequently, developing a strong commitment and connectivity to the religious beliefs of his community. His preliminary value orientation appears to have been predominantly structured in the milieu of the orphanage as the initial place for his social interaction. The orphanage belonged to a particular religious community hence the religious environment deeply influenced his upbringing and values orientation. This following statement taken from his interview reflects his personal values orientation and the motivational bases for acquiring such values:

Every time, when I was on the road walking alone, something from inside me was praying, "Lord I want to serve you; I want to serve your people." How? I don’t know. This was a continual prayer inside of me; it was not that I was doing it willingly.... Sometimes, I would say, "I am not going to do this but every time some kind of force inside me [prevailed otherwise] (Interview, 19/01/2009).

Mr. Barkat frequently pointed towards the divine force: his Lord as the motivation and aspiration for all his activities. To use his own words, "My motivation is my Lord… it says serve the lord with your whole heart, your soul. So that‘s my motivation that I have to serve the lord and serve our neighbours" (Interview, 19/01/2009).

Mr. Barkat is a prominent social worker in his community and resides in a socially and economically unprivileged area. The majority of the community members is economically poor and adhere to unprivileged professions. He and his school aim to educate the children of this particular community. Mr. Barkat seems deeply concerned for the low socio-economic status of the community inhabitants and is passionately determined to improve the status of his people by primarily focusing on educating the young. He seems to understand the plight of a poor family. As a reformer, he strives for an improved future for the community children through education:

Because I have grown up as an orphan child and I have seen all the mess in my life, many things we wanted to get it but we couldn’t…, but you see you are an orphan child wishing for a [better life] … we didn’t get it because we are poor. I [realized] that [this was] something I have to do for the community (Interview, 19/01/2009).

“The Al-Azhar School” and “Mr. Hayder”

The Al-Azhar school, established in 1982, is part of a community-based schooling system aimed at providing quality education to the local children. The school began as pre-primary and has expanded to an institution offering both Matric and O-Level systems of education under the supervision of a board of trustees. Currently, there are 86 staff members including teaching staff and non-teaching staff, serving 653 students from pre-primary to class O Level. Mr. Hayder is the school‘s headmaster.

The community of Mr. Hayder resides in a privileged area of Karachi and most of its citizens are business entrepreneurs. Hence, he aspires especially for the young children to follow the communal traditions with a sense of pride and belonging. Mr. Hayder‘s initial upbringing took place in a middle-class business family who strongly believed in upholding the communal traditions of and providing services to the community proper. Mr. Hayder feels proud to be part of his community and at times showed his complete selfless devotion to serving its needs. This sense of service, in turn, generated self motivation. He opined that: "The strongest motivation is, I believe, that this is my khidmat (service). This khidmat concept always motivates me" (Interview, 21/01/2009). Mr. Hayder regards people from his community as his role models, maintaining that, "A role model is always in our mind. I have seen my senior teachers, the way they were working when I was in Jamia (Community University). Always I had a dream ... that I have to be like them" (Interview, 21/01/2009). He gained his masters degree from his community-based university and attributes the formation of his values from the communal values at the university.

The Influence of Personal Values on Leadership Practices

School Culture

The school culture seems to reflect many of the values Mr. Barkat professes. He attempts to inspire his teachers to value the services to God and to the community, consequently constructing a particular school culture which regards teaching as a contribution to the sacred cause of educating the young generation of his community.

This is not a place where you are going to come and do a job. You are here to serve. If you think you can serve the community and the Lord then this is the place for you…. Every time we sit here – 7:45 to 8 o’clock is our devotion time – the staff is here to pray and definitely while praying we ask the Lord to help us in serving Him and the community and work for the sacred cause of educating the youth (Interview, January 19, 2009).

Mr. Barkat is enthusiastic and committed to acting as a role model for both his teachers and students (Kouzes and Posner, 1997). He firmly believes that: "I have to be the inspiration for my staff. I have to look after them, take initiatives …I serve my staff and then I expect them to serve the children" (Interview, February 9, 2009).

It appears that Mr. Barkat strongly relies on the inculcation of a distinctive school culture which is predominantly based on service to God and to the community. All members of the school community are expected to realize that they are part of a team which is striving for the attainment of a sacred cause.

With respect to Mr. Hayder, the school culture seems to predominately reflect the communal values of the immediate religious community. The inspirational prayers in the morning assembly, the typical communal dress code for both teachers and students, and the particular eating and drinking style all mirror these values. In an informal discussion, Mr. Shabir, a teacher, mentioned, "See – this is not only a school. It is the extension of the home culture and we are proud of it" (Observation, February 16, 2009).

During morning prayer, Mr. Hayder and his teachers dress in the traditional garb and strictly follow the rules observed by their community, reflecting their efforts to be role models of communal culture (Observation, February 16, 2009). It appears that Mr. Hayder is inspired to cultivate a school culture which reflects both his personal and the communal values.

Both the cases of Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder appear to agree with Campbell, Gold, and Lunt (2003), who found that in different ways, the ethnic, religious, and socio-economic characteristics of the local communities influence processes and practices within their respective schools. Further, conformity is demonstrated by the values exhibited by the school leaders who, in turn, expect their staff to replicate same.

School Structure

In the Blessing School of Mr. Barkat, the curriculum is an amalgamation of both secular and religious instruction. In this regard, Mr. Barkat explains,

This is not a place where you are going to come and do a job. You are here to serve. If you think you can serve the community and the Lord then this is the place for you…. Every time we sit here – 7:45 to 8 o’clock is our devotion time – the staff is here to pray and definitely while praying we ask the Lord to help us in serving Him and the community and work for the sacred cause of educating the youth (Interview, January 19, 2009).

The school structure of Mr. Barkat is predominantly aimed at detaching the students from the local culture in order to make them change agents for the future. His rationale for building such a structure is to provide a safe environment to prevent the students from reverting to the local culture. Campbell, Gold, and Lunt (2003), support this point of view by maintaining that school leaders are seeking to work in ways which develop their students and encourage community development, often involving attempts to change values and practices in the community rather than mirroring or reinforcing them. Succinctly, Mr. Barkat appears to strive for developing a distinctive school structure, in which the curricula, parental involvement, student nurturing, and teacher empowerment have their own particular characteristics which are predominantly in conformity with his personal values.

In the case of Mr. Hayder, the school system has embedded religious and secular education into a single package (School Website Analysis). In an informal discussion about such a distinctive curriculum, Tahira Bahan, a section head, stated: "We want our students to carry a single compact briefcase in life, instead of two separate briefcases: one for Din [religious] and one for Dunya [secular]" (Observation, January 21, 2009). Mr. Hayder appeared to be in direct connection with the processes of teaching and learning by personally teaching classes and developing a system of coordination among the section and department heads as well as with the teachers. Monitoring and guidance seemed to be his forte as demonstrated during his regular classroom observations and weekly meetings with all the teachers. "I did not stop my teaching. I teach and like to teach…in this way I develop an interaction with the students and they tell me many things. The teachers also come in close contact. You see it also helps in monitoring" (Interview, January 21, 2009).

There are section heads, subject coordinators, and teacher leaders exercising their responsibilities at various levels. Mr. Hayder seems to value consulting his subordinates as well as his higher authorities before making any decision, explaining that: "I always consult with the concerned section heads and ask, ‗I am planning to do this, what is your opinion?‘" (Interview, January 21, 2009). Consequently, Mr. Hayder seems to play an active role in establishing a school structure which is in line with the school organizational values, the broader community values, and his personal values. Thus, in concluding that the school structures reflect the respective personal values of Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder, it is equally true that such values are inextricably influenced by the broader community values.

Relationship with the Community

Mr. Barkat‘s critical role as a reformist and a change agent (Kouzes and Posner, 1997) enables him to cultivate an intimate and compassionate relationship with his community. Elaborating on his role in bringing about an improvement in the life of his community, he maintained:

I mean overall our role in the development of community is that we are educating these children. When they will go back to their houses each and every family will have more educated people in the family and then the whole community will start developing. Not only financially but morally and ethically they will be educated and will start developing (Interview, February 9, 2009).

Mr. Barkat appears to be involved in the social life of his community. As a prominent social worker, he is not only in close contact with the local community for the education of their children but also for resolving other emerging social issues in the society. In this regard Mr. Barkat narrated an event in the following lines,

They [his community people] don’t know how to live a better life and help each other… last Sunday there was a fight. One party was taken by the police to the police station and in the morning, I called both parties and I sat with them and made them reach reconciliation (Interview, February 9, 2009).

As an inspired member of his community, Mr. Hayder seems to believe in cultivating a deep- rooted and wide-ranged interaction with the parent community and the two levels of management authorities in the school. His interaction with the parent community is not confined to the premises of the school. He remains in contact with parents at various social gatherings and occasions which take place in the community:

This school belongs to the community; we only allow our community children to come and study in this school so our biggest stakeholders are our community members …We also meet in community occasions. They are from the same community, but at the same time, they are parents also so I try to be very polite with them and always consider parents as a priority (Interview January 21, 2009).

Apart from informal interactions with the parent community at social gatherings, Mr. Hayder has established a formal system of keeping parents engaged:

We have a yearly plan in which we arrange three or four open days with parents to discuss problems. Apart from those open days, we have a science fair when we call parents. We organize an annual sports day and at this juncture we call parents. We organize different stage programmes, we started two years back… Apart from this, if we face any behavioural problem, academic problem, we involve parents and we discuss (Interview February 16, 2009).

Succinctly, the personal values of both the principals appear to be influencing the nature and kind of relationship they cultivate with the external community. In both the cases of Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder, the findings appear to be in line with England and Lee (1974) who have pointed out that the values affect leaders‘ perceptions of situations and play a role in their interpersonal relationships.

Conclusions

The Model of Influence and Regulation

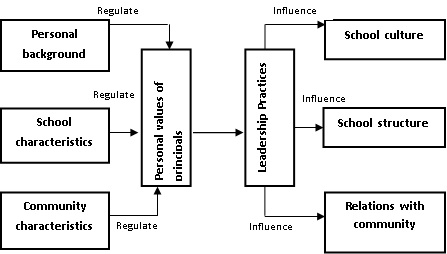

Based on the study findings, a contextual model is proposed to illuminate the factors that regulate the personal value orientation of the principals and the translation of these values through the art of leadership in developing the school culture, structure, and the relationship with the surrounding community. In Figure 1, the first level shows how the personal background of the principals, the organizational characteristics of their respective schools, and the characteristics of the target community regulate the personal value orientation of the principals. The second level illustrates how the personal values of the principals affect certain areas of school life such as the school culture, school structures, and relationships with the parent community by influencing their leadership practices.

The personal background emerged as the prominent regulator for both Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder in acquiring their personal values (Law, Walker & Dimmock, 2003). As an orphaned child, Mr. Barkat‘s personal values were predominantly shaped and ordered in the milieu of the orphanage as the initial plane for his social interaction (Begley, 2003). The orphanage belonged to a particular religious community; hence the religious environment deeply influenced the upbringing and value orientations of Mr. Barkat. Conversely, Mr. Hayder experienced his initial nurturing in a middle-class business family who strongly believe in upholding the cultural traditions and services of their particular community. Accordingly, his value orientations have been chiefly shaped by his family and the surrounding community (Begley, 2003). He feels proud to be a part of his community and at times showed his complete self-devotion to the services of his community. In both cases, the orientations of their personal values seem strongly rooted in their respective personal backgrounds.

The economic status of the community seems to be another element that regulates the valuation process of these principals. In the case of Mr. Barket, he and his Blessing School are part of a community which is predominantly comprised of a low socio-economic population. Therefore, his personal values are primarily focused on changing the existing status of his community. In contrast, Mr. Hayder and his Al Azhar school are part of a community which enjoys a comparatively higher socio-economic status and possesses an organized structure of communal tradition. Hence, with a sense of pride, he values devotion and services to his community. The basis for their value orientation of the two principals seems to be in a continuous struggle for balancing between cultural identities, enduring traditional values, and the modern market demands for economic development of their communities (Sapre, 2000). It seems that due to increasing globalization, the market model of educational leadership is also playing a part (Portin, 1998) in the value orientation of these school leaders but did not emerge as strong as the religious and cultural factors. Arguably, the value dimension obtained from this study may not be similar to that of the developed world (Routamaa and Hautala, 2008).

The organizational characteristics of the school emerged as another regulating factor for the acquisition of personal values by Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder (Law, Walker, and Dimmock, 2003). The Blessing School is independently operating as a smaller entity. Although there is a board of trustees elected by the local community, the personal values of Mr. Barkat remain the dominating, guiding force. In contrast, the Al Azhar School is part of an international schooling system. Hence, the management hierarchy, distribution of leadership, and policies and procedures are comparatively well-defined. Therefore, Mr. Hayder‘s personal values, at times, showed their alignment with the organizational values.

The data revealed that the personal values of both the principals appear to be influencing the nature and kinds of relationships they cultivate with the external community. The school structures were predominantly in line with the personal values of Mr. Barkat and Mr. Hayder. Similarly, the school culture seems to reflect many of the values the two principals uphold. The personal values of these school leaders seem to affect their perceptions of situations and play a role in their interpersonal relationships. In both cases, yet in different ways, the ethnic, religious, and socio-economic characteristics of the local communities influence processes and practices within the school. These school leaders convey their values in all their actions and expect their staff to conform accordingly.

References

Begley, P.T. (1999). Value preferences, ethics and conflicts in school administration. Values and educational leadership, 237-252. New York: State University of New York Press.

Begley, P.T. (2001). In pursuit of authentic school leadership practices. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 4(4), 353-365.

Begley, P. T. (2002). Western-Centric Perspectives on Values and Leadership. School Leadership and Administration, 45-61. London: Routledge Falmer.

Begley, P.T. (2003). In pursuit of authentic school leadership practices. The ethical dimension of school leadership, 1-12. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative Research for Education: An introduction to theory and methods, 3rd Ed., Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Branson, C. M. (2005). Exploring the concept of values-led principalship. Leading & Managing, 11 (1), 14-31.

Campbell, C., Gold, A & Lunt, I. (2003). Articulating leadership values in action: Conversations with school leaders. International Journal for Leadership in Education, 6(3), 203–221.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, mixed method approaches. 2nd Ed. California: Sage Publication.

D, Arbon, T., Duignan, P., & Duncan, D. (2002). Planning for future leadership of school: An Australian study, Journal of Educational Administration. 40(5), 469-485.

England, G.W. & Lee, R. (1974). The relationship between managerial values and managerial success in the United States, Japan, India, and Australia. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(4), 411-19.

Gurr, D. Drysdale, L. & Mulford, B.(2006). Models of successful principal Leadership. School Leadership and Management, 26(4), 371-395.

Hodgkinson, C. (1978). Towards a philosophy of Administration. New York: St. Martin‘s Press.

Hodgkinson, C. (1999). Foreword. In P.T. Begley (Ed.), Values and educational leadership (pp. xi- xiii). New York: State University of New York press.Hodgkinson, C. (1999).The will to power. Values and Educational Leadership, 139-150. New York: State University of New York Press.

Johnson, H., McCreery, E., & Castelli, M. (2000). The role of head teacher in developing children holistically- Perspective from Anglicans and Catholics, Educational Management and Administration, 28(4), 389-403.

Khaki, J. (2005). Exploring beliefs and behaviours of effective head teachers in government schools in Pakistan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Canada.

Kouzes, J. M. and Posner, B. Z. (1997). Leadership Practices Inventory [LPI]: Participant’s Workbook, 2nd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Pfeiffer.

Law, L. Walker, A. & Dimmock, C. (2003). The influence of principals‘ values on their perception and management of school problems. Journal of Educational Administration, 41( 5), 498-523.

Leonard, P. T. (1999). Examining Educational purposes and underlying value orientations in schools. In P.T. Begley (Ed.), Values and educational leadership, 217-236. New York: State University of New York Press.

Leithwood, K., Steinbach, R. and Raun, T. (1993). Superintendents‘ group problem-solving processes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 29(3), 364–391.

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education, California: Jossey-Bass.

Portin, B. (1998). International Challenges and Transitions in School leadership, International Journal of Educational Research, 29(4), 293-391.

Routamaa, V and Hautala, T. M. (2008). Understanding Cultural Differences: The values in a Cross Cultural Context. International Review of Business Research Paper, 4(5), 129-137.

Ryan, J. (1999). Beyond the veil: moral educational administration and inquiry in a post-modern world. In P.T. Begley (Ed.), Values and educational leadership, 73-96. New York: State University of New York Press.

Sapre, P.M. (2000). Realizing the potential of leadership and management: towards a synthesis of Western and indigenous perspectives in the modernization of non-Western societies. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 3(3), 293-305.

Shafa, M. (2003). Understanding how a government secondary school head teacher addresses school improvement challenges in the Northern Areas of Pakistan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Canada.

Walker, A & Dimmock, C.(2000). Exploring principals‘ dilemmas in Hong Kong :Increasing Cross Cultural Understanding of school leadership. International Journal of Educational Reforms, 8(1), 15-24.

Yin, A. K. (2003). Case study research design and method, (3rd Ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Biography

The author is a faculty member of the Professional Development Center North (PDCN), a component of the Aga Khan University, Pakistan. He is also a member of the Research and Policy Studies of the Institute for Educational Development of the University. Having experience of more than fifteen years in the profession of teaching and learning, the author is engaged in educational research, particularly in the field of human values and student behaviour management. In this connection he has disseminated many research works through international journals focused on educational development.

Contact: sharifullah94@yahoo.com